Early Rounds

Round 1: The Boxing Board

“The truest competition in all of sports still is two guys in a boxing ring,” observed the famed football coach and analyst John Madden in 2012 (Dave Newhouse, Before Boxing Lost Its Punch, Foreword by John Madden (ebook 2012)).

At the writing of this sentence, in 2013, ESPN.com is reporting that its panel of experts has ranked boxing as the world’s most difficult sport. Each panelist independently ranked sixty sports in terms of the following categories:

1. Nerve—defined by ESPN as the “ability to overcome fear.” For this category, boxing received an 8.88 out of 10.

2. Endurance—boxing received an 8.63 per the “ability to continue to perform a skill or action for long periods of time.”

3. Power—boxing received an 8.63 per the “ability to produce strength in the shortest possible time.”

4. Durability—boxing received an 8.5 per the “ability to withstand physical punishment over a long period of time.”

5. Strength—boxing received an 8.13 per the “ability to produce force.”

6. Hand-eye coordination—boxing received a 7.0 per the “ability to react quickly to sensory perception.”

7. Speed—boxing received a 6.38 per the “ability to move quickly.”

8. Agility—boxing received a 6.25 per the “ability to change direction quickly.”

9. Analytic aptitude—boxing received a 5.63 per the “ability to evaluate and react appropriately to strategic situations.”

10. Flexibility—boxing received a 4.38 per the “ability to stretch the joints across a large range of motion.”

Thus boxing received a total score of 72.4 out of 100 and a number-one ranking. By contrast, martial arts received a total score of 63.4 and a number-six ranking. Martial arts received higher scores in analytic aptitude (6.88) and flexibility (7.0).

Naturally the regulation of boxing, with the goals of safety and honesty, is part of the sport. Dealing with regulators isn’t a skill rated by the ESPN panel. There’s no rating of the skill of dealing with television networks, which may be doing the matchmaking. There’s also no rating of the skill of dealing with the relatively few but prominent reputed criminals, and some convicted, within boxing.

Effective regulation takes boxing experience but also dignity and street smarts. It takes a unique set of skills to use kid gloves with the various characters in the fight game, all the while making sure the goals of safety and honesty aren’t compromised.

In the spring of 1976, Governor Wendell Anderson appointed Jim O’Hara to the Minnesota Board of Boxing, which then regulated boxing in the state. Jim was fifty years of age. Don Riley, sports columnist for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, applauded the appointment. Murray McLean, Jim’s former boxing manager, predicted confidently: “He won’t ask how tough is the problem, [Jim will] only say, ‘Let’s get at it’” (McLean is quoted by Don Riley, “Don Riley’s Eye Opener,” St. Paul Sunday Pioneer Press, June 13, 1976).

Shortly after Jim’s appointment, there was a vacancy in the board’s office of executive secretary. Jim was interested, but there was another gentleman with boxing experience at Harvard who appeared to have the inside track. Before the vote to elect the new executive secretary, the other candidate presented an eloquent speech on why he should be elected. When it was Jim’s turn, he pointed out what was going on at a certain gym in a certain big city. “You elect me,” he said, “I’ll clean it up.”

By tradition, the executive secretary was elected from among the incumbent boxing commissioners. A candidate officially threw his hat into the ring by agreeing to resign his seat if the votes were there to elect him. So the governor appointed the commissioners. The commissioners then elected their paid advisor (known as the executive secretary) from among themselves while naturally retaining the power to remove and replace.

You know Jim was grateful when he was elected. The Boxing Board was giving a shot to a local ex‑fighter from the streets when it had another excellent candidate. They say the other gentleman, who never resigned his seat on the board to be considered for executive secretary, threw in the towel so Jim was effectively unopposed in the end. (It was a little awkward when the erstwhile candidates ran into each other the night of the vote at the Blue Horse Restaurant on University Avenue in the Midway District of St. Paul. Closed in 1991, the Blue Horse was a regular spot for state legislators.)

Jim was the immediate successor of Larry McCaleb who had died July 28, 1976. McCaleb had succeeded Fay Frawley who had just retired June 15, 1976. Fawley had succeeded Jack Gibbons who had retired October 28, 1975. Gibbons had succeeded George Barton who had died May 8, 1969.

McCaleb had served four years, including his tenure as a commissioner; Frawley, twelve years; Gibbons, nineteen years; and Barton, twenty-seven years.

The executive secretary of the Boxing Board was expected to be one of the most dynamic forces within Minnesota boxing. Jim fit the bill for the next quarter century.

The office was a paid, part-time position. Eventually the state offered Jim a full-time position to do all the work that needed to be done, but he declined. He offered to get everything done while getting paid on a part-time basis, and he did.

A paid advisor didn’t cost the state an arm and a leg. When Jim got the job, the annual pay was $6,ooo, excluding benefits. If you figure a conservative 4 percent annual inflation rate, $6,000 in 1976 might be about $27,000 in 2015 dollars. He was flat-out honored to hold the post that had long been held by persons who know boxing inside out.

During Jim’s tenure, there were a good number of world title bouts within Minnesota’s borders. These bring-it-on events—for a world title, mind you—were huge, including:

Larry Holmes vs. Scott LeDoux, World Boxing Council (WBC) Heavyweight World Championship, July 7, 1980, Metropolitan Sports Center, Bloomington. Muhammad Ali was ringside as LeDoux was stopped in the seventh. The 6,491 spectators paid $253,000, the standing Minnesota record gate, which might be about $985,338 in 2015 dollars (using a 4 percent annual inflation rate). The previous year, LeDoux had faced both Ken Norton and Mike Weaver at the MET Center, drawing with Norton and getting decisioned by Weaver. LeDoux vs. Weaver was for the United States Boxing Association (USBA) heavyweight title. Jim was a vice president of the USBA.

Mike Evgen of St. Paul vs. Louie Lomeli of Illinois, International Boxing Organization (IBO) Light-Welterweight World Championship, April 9, 1992, Roy Wilkins Auditorium, St. Paul. In this inaugural title fight for this weight division, Evgen got the crown in a twelve-round split decision.

Will Grigsby of St. Paul vs. Carmelo Caceres of the Philippines, International Boxing Federation (IBF) Light-Flyweight World Championship, March 6, 1999, University of Minnesota Sports Pavilion, Minneapolis. “Steel” Will got the unanimous twelve-round decision to retain the Light-Flyweight World Title he’d won the previous December. In 1996, he’d captured the USBA Flyweight Title in a twelve-rounder held in Rochester, Minnesota.

For every world title bout held in the state with a Minnesota fighter, imagine how many amateur and nontitle pro bouts there are in the state. The answer is a knockdown number. With all the training and planning that goes into any match, there’s a lot of boxing going on to be sure.

With a 1934 St. Paul diamond champion belt found in his desk after his passing, Jim may’ve had seventy years in the fight game. He certainly had sixty. More importantly, thanks to the Golden Gloves and trainers and managers like Ray Temple and Murray McLean, Jim learned to keep to the high road, which he defined as integrity. “Integrity’s all you got,” he said. “Once it’s gone, you got nothing.”

Terry Collins, writing for the Minneapolis Star Tribune, remarked: “He was the voice of reason in a sport where toughness, egos and big paychecks reign supreme. He also was legendary for settling disputes between promoters and prizefighters” (Terry Collins, “Jim O’Hara Dies; He Ran the State Boxing Board,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, January 21, 2002, page B5, column 1). In 1980, Jim helped settle a dispute between Don King and Larry Holmes when Holmes was the heavyweight champ. See Round 11, “Muhammad Ali.”

Jim also had to be on his toes to anticipate and sidestep disputes within his own ranks, including anything physical, such as when Scott LeDoux and Gary Holmgren served together on the Boxing Board. More than a fan of both Hall of Famers, Jim recognized that as big and tough as LeDoux was, LeDoux better watch himself if Holmgren got mad. “He’s liable to whack him,” intimated Jim with the expression of a dad worried for two sons. While LeDoux was known as the Fighting Frenchman, Holmgren’s moniker was the Hammer. They’ve both been inducted into the Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame, LeDoux in 2010 as part of its inaugural class and Holmgren in 2013.

“He was a great mediator and diplomat,” said Joe Azzone of Jim (Azzone is quoted by Terry Collins, supra). A past chair of the Boxing Board and longtime leader in the Golden Gloves, Azzone knew Jim just about as well as anyone. They’d grown up together.

Using street smarts, Jim could read people. There wasn’t any point in bluffing or lying because he could tell if you were. “I always thought Jim was the wisest guy I ever met,” commented referee Denny Nelson. “He knew how to handle people” (Nelson is quoted by Jim Wells, “Jim O’Hara, 76, Boxing Official,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, January 19, 2002, Obituaries, City Edition.) In an email dated January 9, 2013, Nelson assigned Jim a top ranking for his work with the Boxing Board. “Over the years I have worked with six executive secretaries of the Minnesota boxing commission,” wrote Nelson. “No one could handle the job like Jim.”

A globetrotter in his third-man capacity, Denny has refereed many a world championship bout. His son Mark Nelson, also a globetrotter, is his equal as a fight handler. You can say that again that Jim thought the world of these two. He knew the boxing ref may well have the toughest officiating responsibility in all of sports. Others have long held this view (Harold Valan, “Fight Referee Harold Valan Calls His Job Toughest of Pro Sports Officials,” The Ring, August 1974, 12).

Not unlike a first-rate referee, Jim protected boxers who might otherwise have been severely injured or who might even have lost their lives in the ring. Safety was his mantra: “Nobody’s going to die on my watch [from lack of safety precautions].” He knew boxing history and what was possible. For example, in 1915, John Simmer, nineteen years of age, died in an unregulated bout at Matt Dietsch’s hall in St. Paul. The match was allowed to continue in the fifth round even though Simmer was groggy and defenseless. After he hit the canvas, he was allowed to remain there unconscious for 30 minutes before medical aid was sought (Clay Moyle, Billy Miske: The St. Paul Thunderbolt 18-19 (Win By KO Publications 2011)).

Jim was accustomed to the periodic, if inevitable, wrath of promoters and professional fighters. He appreciated they were businessmen who naturally advocated in all forums available to them. Nonetheless, his immovable recommendation to the Boxing Board was that it err, if at all, on the side of protecting the fighters, even if the fighters sincerely believed they didn’t need protection. If a proposed bout didn’t add up in the safety-first view of the Boxing Board, the bout wasn’t approved.

Jim was called every name in the book, as you can imagine, during his sixty years in the busted-nose fraternity, perhaps never more vehemently than during his twenty-five years as the face of the Minnesota Board of Boxing.

If the other parties were open to his help, he offered assistance wherever he could. Tom Powers, columnist for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, said it best:

O’Hara, as much a part of the fabric of St. Paul as the cathedral or the capitol building, worked with promoters, handlers and fighters, always gently steering them in the right direction. He could tell them where to get proper health insurance as easily as he could recommend a qualified referee. (Tom Powers, “Boxing Lost a Friend with O’Hara’s Passing,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, January 23, 2002, page D1, column 2.)

Jim advocated before the state legislature for the budget necessary to maintain safety and honesty in Minnesota boxing. A comparison he liked to draw when he appeared before a legislative committee was the cost of incarcerating an individual in prison versus the cost of assuring a positive activity for Minnesota’s youth.

His vision was to fill the boxing gyms with young people who, through boxing, learn goal-setting and discipline, which leads to self-control and ultimately good citizenship. From personal experience, he knew that boxing can provide a way out of a potential life of trouble—not so much from the purse that a bout might bring but from the discipline gained. “Kids want discipline,” said Jim. “They really respond to it in the gym.”

Terry Collins of the Minneapolis Star Tribune put it this way: “His goal was to recruit community leaders to help youngsters in the Golden Gloves program stay in the ring, in school and out of trouble. He also was instrumental in establishing a boxing program at Stillwater prison” (Terry Collins, supra).

Jim believed that if boxing went unregulated, safety would be compromised, which was unacceptable, and unethical influences from outside the state could threaten the honesty that Minnesota boxing had stood for since the days of George Barton. Jim believed that without safety and honesty, boxing would cease to be a positive alternative for youth and would become a joke.

In 2012, this writer had the opportunity to talk to a fifty-eight-year-old ex-fighter living on the streets of Anchorage, Alaska. He'd been a bare-knuckle fighter for too many years. His is a cautionary tale for the guardians of the sport of boxing. In his youth, in the early 1970s, he boxed in the Golden Gloves. When his record reached 13 and 0 as an amateur welterweight (147 lbs. max.), he was approached by a guy claiming to represent a big city manager.

The fellow told the prospect that, as a pro, he’d be expected to carry opponents in the ring from time to time and then asked: “After you carry five rounds, what will you do when you’re told to lie down?”

“I’d knock out my opponent,” he replied.

“Wrong answer,” was the judgment. “You’ll never make it as a pro.”

If there’s no verifying that story, there’s no malarkey in El Caballo Blanco, the protagonist in Christopher McDougall’s acclaimed book Born to Run. Before getting into running Caballo, who was born in 1954, did time in the fight game’s underworld:

He was born Michael Randall Hickman, son of a Marine Corps gunnery sergeant whose postings moved the family up and down the West Coast.

* * *

After high school, Mike went off to Humboldt State to study Eastern religions and Native American history. To pay tuition, he began fighting in backroom smokers, billing himself as the Gypsy Cowboy. Because he was fearless about walking into gyms that rarely saw a white face, much less a vegetarian white face spouting off about universal harmony and wheatgrass juice, the Cowboy soon had all the action he could handle. Small-time Mexican promoters loved to pull him aside and whisper deals in his ear.

"Oye, compay," they’d say. "Listen up, my friend. We’re going to start a chisme, a little whisper, that you’re a top amateur from back east. The gringos are gonna love it, man. Every gabacho in the house is going to bet their kids on you."

The Gypsy Cowboy shrugged. "Fine by me."

"Just dance around so you don’t get slaughtered till the fourth," they’d warn him—or the third, or the seventh, whichever round the fix had been set for. The Cowboy could hold his own against gigantic black heavyweights by dodging and clinching up until it was time for him to hit the canvas, but against the speedy Latino middleweights, he had to fight for his life. "Man, sometimes they had to haul my bleeding butt out of there," he’d say. But even after leaving school, he stuck with it. "I just wandered the country fighting. Taking dives, winning some, losing but really winning others, mostly putting on good shows and learning how to fight and not get hurt." (Christopher McDougall, Born to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the World Has Ever Seen, Chapter 32 (Alfred A. Knopf 2009), Kindle Edition.)

Growing up in an era when St. Paul was known for its corruption, Jim was taught to have no tolerance for it. See Round 4, “The O’Hara Name & St. Paul.” Dirty pool turned his stomach. He could tell if a fighter was carrying the other, and he could tell when someone took a dive.

Fixed matches are impossible to prove unless you get a confession, and even then you may be faced with conflicting testimony. But everyone knew he could read a fight and size up what was going on, and thus he helped deter the few bad apples who might have tried to come to Minnesota to play their games.

With candor and humor, Jim acknowledged the pressure to present the boxing audience with a good show. But, directed at the fighters, he warned: “I carried Timberjack Wagner and they carried me out of the ring.” (“Don Riley’s Eye Opener,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, June 7, 1976.) In October 1953, the six-foot-three Wagner, in his professional debut no less, defeated Jim by TKO in the sixth. See Round 7, “Boxing Record.”

A sobering reminder of how criminals may extend into boxing, if unchecked by state boxing commissions, is the 1930–1935 story of the 268 lb., six-foot-five-and-a-half Primo Carnera. He was propped up as the world heavyweight champion, a scam on him as well as the public (Paul Gallico, “Pity the Poor Giant,” 1938). Gallico was a founder of the Golden Gloves. His essay on Carnera is included in George Kimball and John Schulian, At the Fights: American Writers on Boxing (Library of America 2011, Kindle Edition).

Carnera had skills, mind you. In September 1932, he fought a ten-rounder at the St. Paul Auditorium against six-foot-four Art Lasky, the local favorite out of Potts Gym in Minneapolis, who you know with Jimmy Potts in his corner held nothing back. Mike Gibbons, the face of legitimacy for Minnesota contenders, was the ref. The verdict was left to the sportswriters, who presumably guarded their independent judgment. Carnera got the newspaper decision. In the midst of the Great Depression, four thousand paid to see an honest fight between giants.

The need to be on the lookout for the shakedown and violence was embedded in Jim’s memory. One of his mentors was promoter Jack Raleigh. Jim felt Raleigh’s pain and anger when Raleigh’s restaurant in Wisconsin was visited by professional thugs with axes and sledgehammers after Raleigh had rebuffed a demand for a piece of the gate of his Kid Gavilan vs. Del Flanigan promotion. With 9,434 in attendance at the St. Paul Auditorium in April 1957, Flanigan got the ten-round decision, while Raleigh got the uninsured loss. About five years earlier, Jim’s closest brother Mike, a heavyweight, died by the gun following a bar fight. See Chapter 3, “The Unspeakable.”

Welterweight champion of the world, 1951–1954, Kid Gavilan is ranked number sixty-one on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar, Boxing’s Greatest Fighters 207 (The Lyons Press 2006)). Del Flanigan was inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 2003.

They say Kid Gavilan had no choice but to work with managers controlled by the Mafia, which promised financial backing and title fights. The head was New York mobster Frankie Carbo (John Paul Carbo, born 1904, Lower East Side). Known as the “underworld commissioner,” Carbo controlled the lightweight, welterweight, and middleweight titles for twenty years until his arrest in 1959 (David Remnick, King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero, Chapter 3 (Vintage Books 1999), Kindle Edition).

One day, a State of Minnesota employee made an appointment with Jim. She said she was writing his job description and wanted help.

“Write this down,” Jim offered. “When it happens, I know what to do.”

“I’m serious,” she replied.

“So am I,” said Jim.

Jim’s point was that just as the boxer enters the ring with a fight plan, you obviously plan. But when the unanticipated happens, as it surely will, the executive officer of the Boxing Board must have the experience and street smarts needed.

In 1980 when Larry Holmes fought Scott LeDoux in Minnesota, television personality Howard Cosell did the live broadcast. One of the best sportscasters of all time, Cosell loved boxing. You could tell from the post-fight interviews that he thought it’d been a good fight, including in terms of its end in the seventh after it became one-sided. But then on November 26, 1982, after Holmes was allowed to pop Randall “Tex” Cobb the entire fifteen-round distance in their infamous mismatch, Cosell walked away disgusted. With over three decades in boxing, he’d decided he’d called his last pro fight.

Cosell no longer had faith in the ability of boxing commissions to work with promoters to avoid the mismatch and, as a fail-safe, stop a fight when it’s become uncompetitive. “Uncompetitive” means a fighter is unable or unwilling to protect himself. Wearing his hat as a boxing official, Jim believed a bout may need to be stopped even where (a) the fighter and his corner want the fight to continue, (b) the fighter can take a punch, and (c) theoretically the fighter could still win by KO. “Fantasyland” is what Jim called (c). Whether a contest has become uncompetitive is a judgment call based on the combined experience of the boxing officials regulating the fight.

Jim had long put his money where his mouth was. In 1949, he’d bowed out of an exhibition match with Joe Louis even though any show with arguably the greatest heavyweight of all time would’ve helped his resume. See Round 10, “Joe Louis.”

Love him or hate him, Cosell believed he had to take a stand. While Holmes delivered the undisputed best jab in the business and Cobb made his case for being the undisputed king of toughness, the performance of the ref and other officials was disputable. They’d done nothing but watch fifteen lopsided rounds thirteen days after the Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini vs. Deuk-Koo Kim bout. Kim died from that lightweight championship fight, which had gone into the fourteenth round. After November 1982, the WBC limited all title contests to twelve rounds; Jim advocated for a ten-round limit.

If he ever measured his words, Cosell threw away the yardstick when he later said:

Professional boxing is no longer worthy of civilized society. It’s run by self-serving crooks, who are called promoters. . . . Except for the fighters, you’re talking about human scum. . . . Professional boxing is utterly immoral. It’s not capable of reformation. I now favor the abolition of professional boxing. You’ll never clean it up. Mud can never be clean. (Howard Cosell quoted in Joyce Carol Oates, On Boxing (HarperCollins e-books 2006), Kindle Edition (contains various essays by Oates)).

For Jim, who was the model promoter? He was fortunate to have been close to several in his formative years in the game. There’s Emmett Weller, inducted into the Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame in its second year. Weller cared more about the fighters than himself. The list of exemplars in the promotion side of boxing also includes Jim’s good friends and mentors Billy Colbert, Lou Katz, Spike McCarthy, Murray McLean, Jack Raleigh, Ben Sternberg, and Mike Thomas.

With a clear vision for safety and honesty at every level of boxing, Jim strove to keep the sport moving forward after that fateful November in 1982. Minnesota became known as the “sissy state,” as Jim put it, because of its emphasis on safety, including its standing eight count as of 1978 and its requiring amateurs to wear head gear as of 1983. Jim advocated that no bout in the world should be sanctioned beyond ten rounds.

If the Holmes-Cobb bout was a low point in boxing, countless dedicated men and women labored on. For his part, Jim served the sport another nineteen years. What kept him going? You couldn’t say it was the money or power or honors.

A successful businessman, he could’ve retired comfortably in 1989, for example, when Kitty (his wife) retired from Control Data. It wasn't power over mighty warriors and their handlers that kept him going. Nor was it trying to match George Barton's twenty-seven years as Boxing Commissioner.

Put it this way: a poor, uneducated street kid with a German name, James J. Ehrich, had thrown in his lot with belters. It was only natural to keep going.

You'd be right to say the sport energized the man who came to be known as Jim O'Hara. But it wasn't just his love of sport and his ability to see art in the sweet science. With his own life being one of redemption, he was energized with hope that he might make a positive difference in the lives of individuals as others had for him.

So he continued to answer the bell, and there wasn’t a part of being on the Boxing Board team that he didn’t love. He particularly enjoyed working with the many dedicated Boxing Commissioners, including Fred Allen, Joe Azzone, Howard Bennett, Dave Bloomberg, Nick Castillo, Jerry Coughlin, Erwin Dauphin, Danny Davis, Harry Davis, Robert Dolan, Gary Erikson, Donny Evans, James Farelli, Pete Filippi, Patrick Foslien, Val Goodman, Wally Holm, Gary Holmgren, Arthur Holstein, John Kelly, Judy Klammer, Stan Kowalski, Scott LeDoux, Vern Landreville, Robert Mack, JoAnn McCauley, Tom Mosby, Richard H. Plunkett, Robert Powers, George Reiter, Richard Schaak, Billy Schmidt, Les Sellnow, Robert Thompson, James Trembley, Clem Tucker, and Dan Wall.

One of the best parts of the job for Jim was interacting with kids of all ages, including spectators. Amid the managed chaos of a boxing show, he joked with youngsters, especially when he saw a clear opening. One evening in the 1990s, Boxing Commissioner Dan Wall brought his son, Nolan, to the fights. Nolan was twelve or thirteen. When one of the matches was about to be cancelled due to a boxer’s failure to show in time, Jim marched up to Nolan and said: “What size shoe did you say you wear? Great! We have a pair that will fit and the trainers will get you fixed up with trunks and gloves so you can fill in.”

“Nolan was quite relieved when Jim cracked a smile and gave him a wink,” Nolan’s dad recalled in 2012.

In January 1985, State Representative Phyllis Kahn of Minneapolis was the chief sponsor of a bill to make boxing a crime in Minnesota. Known as H.F. No. 198, her bill read as follows:

Subdivision 1. BOXING, SPARRING, AND KICK BOXING. It is unlawful for a person, partnership, or corporation to advertise, operate, maintain, attend, promote, or aid in advertising, operating, maintaining, or promoting a boxing contest, match, or exhibition. ‘Boxing’ includes sparring and kick boxing but does not include full contact karate.

Subdivision 2. PENALTY. A violation of subdivision 1 is a misdemeanor.

You know Jim brought the fight to anyone who even thought about criminalizing boxing in Minnesota. He debated Representative Kahn, including at least one session broadcast on the radio. In March 1985, he testified before her committee at the State Capitol, not far from where he grew up. Here are notes he made in preparing his remarks:

WHAT DOES AMATEUR BOXING DO FOR THE YOUTH OF AMERICA?

It gives them Confidence, Pride, and Self-Respect.

It is an in-between time — between boy and manhood.

It is not to build professional fighters.

What more can a young person ask for in these troubled times?

A. CONFIDENCE.

B. PRIDE.

C. SELF-RESPECT.

Mothers tell me that their kids are on alcohol and drugs.

What can they do? They are lost.

It is because the kids are lost, not the mothers.

We can only have so many:

Hockey Stars, 6-foot-2.

Football Stars, 240 lbs.

Basketball Stars, 6-foot-8.

Baseball Stars, over 6 feet.

What does a kid 100 to 120 pounds do? He watches and eats his heart out. They are the ones that take to pot to make themselves feel big.

There is trouble ahead for the youth of America if they even consider Banning Boxing.

Look at all the great boxers of the past. The records of their achievements will be looked at like they were illegal.

I ask you, Phyllis, have you ever been at the Radisson Hotel, the St. Paul Athletic Club, or the Decathlon Club in Bloomington, and watched these youth, boys and girls — yes girls — at a boxing event? The cream of Twin Cities society was in attendance and watched a splendid sporting event — not a brutal, savage, out-of-control bout that people are led to believe.

In the end, the politicians didn’t outlaw boxing.

If Jim hated corruption and could read people, he was as shocked and disappointed as anyone when his friend Bob Lee, Sr., founder and president of the International Boxing Federation, fell from grace.

Lee's fall occurred in 1999. The previous year, Jim had said: “It's always been a pleasure to work with Bobby Lee. He always has run a fair and honest organization, and I'm very happy to be associated with him” (“Special Award to Jim O'Hara Deserving One,” 13 (No. 1) IBF/USBA Reporter, 5 (December 1998)).

So Jim believed in Lee and the IBF, the only sanctioning body run by African Americans. Based in Lee's home state of New Jersey, which he saw as the boxing capital of the world, Lee sought to make a difference but lost his reputation fighting corruption charges. A jury found him guilty of money laundering and tax evasion, while he maintained he'd been set up by white promoters and broadcast executives. At sentencing the Judge told Lee to blame himself for abuse of power (Ronald Smothers, “BOXING: I.B.F. Supervision Ends; Founder Gets 22 Months,” The New York Times, February 15, 2001.)

While the IBF and New Jersey dealt with scandal, Minnesota deregulated. Effective July 2001, Governor Jesse Ventura and the State Legislature abolished the Boxing Board without replacement. They said thanks but no thanks to the board, which, with its predecessors, had provided eighty-six years of due diligence in regulating matches and exhibitions.

The Minnesota State Athletic Commission served from 1915 to 1973, and the Minnesota State Boxing Commission served from 1973 to 1975. The first body was lead by George Barton, Mike Gibbons, and Jack Gibbons. The second body was lead by Jack Gibbons. The Minnesota Board of Boxing, lead by Jack Gibbons and Jim, served from 1975 to 2001.

With the goal of shrinking government, the politicians couldn’t stomach the Boxing Board’s $80,000 annual budget. In 1999, State Representative Dan McElroy of Burnsville summed up the mentality that would carry the day: “It’s like somebody said to me, if you can’t abolish the Board of Boxing, what hope is there for controlling the size of government? We don’t have a state soccer board or a state wrestling board” (Mike Mosedale, “Down for the Count: Minnesota’s Boxing Commission Gets Socked in the Kisser,” October 6, 1999, www.citypages.com/1999-10-06/books/down-for-the-count/full/).

If you figure a conservative 4 percent annual inflation rate, $80,000 in 1999 might be about $150,000 in 2015 dollars.

While lobbying against the deregulation of boxing, Jim had one arm tied behind his back, what with heart disease and bladder cancer. When he passed in January 2002 at the age of seventy-six, he believed Minnesota’s laissez-faire experiment in the boxing arena would be short lived. The “French Bomber,” as Jim was known to call Scott LeDoux, vowed to educate politicians on the genuine need for a Minnesota body with rule-making authority devoted to serving the fistic community.

In 2002 and 2003, LeDoux did his advance work for the lobbying campaign ahead. As reported in USA Today in December 2003, one of his concerns was with the toughman fights that had become popular:

"There is no commission to stop this kind of thing, so it’s being done all the time," he said.

"Somebody is going to get killed with these toughman contests. They train for four weeks in the gym and then go out and get their butts kicked." (“Minnesota Boxing Great Seeks Return of State Commission,” USATODAY.com, posted December 26, 2003 7:17 PM.)

In 2006, the politicians demonstrated their agreement with Scott LeDoux by reinstituting oversight by Minnesotans. LeDoux, with eighteen years of experience on the Boxing Board, was appointed by Governor Tim Pawlenty to head the new body.

Sadly, Lou Gehrig’s disease would become LeDoux’s foe. The illness took him in August 2011. He was sixty-two. (Dennis Hevesi, “Scott LeDoux, 62, Gritty Heavyweight Boxing Contender,” The New York Times, August 13, 2011, page D7 (New York Edition)).

No longer can you share a laugh with Jim O’Hara or Scott LeDoux in the flesh. These appointed rule enforcers aren’t visible. But they and Joe Azzone along with so many other men and women of integrity are present in the ideals of safety and honesty still within Minnesota boxing.

Round 2: Dignity & Sportsmanship

Boxing is guts and inspiration, training and planning, footwork and execution. Practitioners are artists. “Boxing is sort of like jazz,” said heavyweight champion George Foreman. “The better it is, the less people can appreciate it” (Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas, The Ultimate Book of Boxing Lists, 13 (Running Press 2010)).

Jim O’Hara emphasized the artistry. “He was one of the very few men who brought dignity to the sport,” wrote Tom Powers, columnist for the St. Paul Pioneer Press (Tom Powers, “Boxing Lost a Friend with O’Hara’s Passing,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, January 23, 2002, page D1, column 2).

Jim pointed to what’s right about boxing—past, present and future—including the countless volunteers challenging young people, win or lose in the ring, to be good family members and citizens.

In terms of dignity within the squared circle, Jim was clear: He didn’t favor the spectacle of tough guys standing toe-to-toe slugging it out where—and here’s the critical point—neither fighter is sidestepping, slipping or deflecting punches to set up the counter. He favored the thinking-man’s game where the boxer who out-thinks the other gets the win, whether by decision or KO.

In the early 1700s, Englishman James Figg, arguably the father of modern boxing, also taught fencing. They say he had a record of 270 wins and only a single loss, all bare knuckle. The “Boston Strong Boy” John L. Sullivan at the end of the 1800s became the first titleholder to prefer gloves (Christopher Klein, Strong Boy: The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan, America's First Sports Hero, Chapter 7 (Lyons Press 2013), Kindle Edition).

Jim compared boxing to fencing, and here the word “parry,” which means to deflect or block an incoming attack, is vividly applicable to both sports.

The boxer is trained to use feints, making the other party miss, and then counter. To avoid or lessen the hit, the boxer is trained to pick off the punch, ride it, and roll with it.

He weaves and ducks to hit. He ties up his opponent. He clinches, getting out of tight spots.

The boxer moves in and moves out and side to side. He circles or dances or runs or gets on his bicycle, working the jab and throwing combinations.

The boxer probes for the tell.

He's got science.

One of the issues for anyone considering a boxing career, according to Jim, is not whether you’re tough but, rather, whether you’re smart. By “smart” he meant the in-the-ring ability to think on your feet, manage time and space, and ultimately hit more than get hit.

Inside the ropes, as on the street, the practitioner of the art of self-defense lives by his wits.

Jim urged all boxers to plan long-term and practice self-preservation, as in the name of Mike Gibbons. Known as the St. Paul Phantom and the Wizard, Gibbons is the father of the St. Paul style of boxing, which Jim called the “School of No Get Hit”. The famous artist LeRoy Neiman grew up a St. Paul street kid like Jim. In his 2012 autobiography, Neiman described the St. Paul style thusly:

The Irish boxers were the champion pugs in those days. They weren’t big punchers — they developed their own slyboots techniques, which is why they called Mike Gibbons "the St. Paul Phantom." He’d been former middleweight champion of the world and was the smartest and fanciest of the fancy footwork school of St. Paul pugilism — on account of he created it. Slip, feint, shift, duck, just jab and counter was their sly style. (LeRoy Neiman, All Told: My Art and Life Among Athletes, Playboys, Bunnies and Provocateurs, Chapter 1 (Lyons Press 2012), Kindle Edition.)

Gibbons had a claim to the middleweight title after the death of the Michigan Assassin, Stanley Ketchel, in 1910. (The Ring Boxing Encyclopedia and Record Book, 19 (The Ring Book Shop 1979)). Gibbons is ranked number five on the list of the top defensive fighters of all time and number ten on the list of the greatest Irish American fighters of all time. Bert Sugar put the lists together with Teddy Atlas (Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas, supra, at 162 and 143).

Gibbons was elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1992. He also is ranked number ninety-two on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar, Boxing’s Greatest Fighters, 314 (The Lyons Press 2006)). A former editor of The Ring magazine, Sugar was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2005. LeRoy Neiman was inducted two years later.

In 1923, Gibbons' brother Tommy would demonstrate his own greatness by becoming the only man to go fifteen rounds with Jack Dempsey. Tommy had confidence from working with Mike, who in 1916 had whipped Jack Dillon, reputed to be just as deadly as Dempsey would ever be. That ten-round newspaper decision at the St. Paul Auditorium irrefutably made the Gibbons name as big as any in fistiana.

With 245 pro fights, Jack the “Giant Killer” Dillon was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1995.

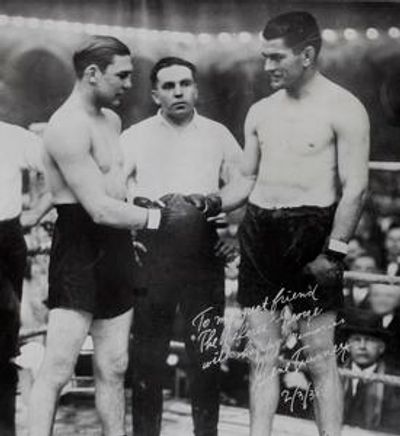

There’s a photograph showing Harry Greb and Gene Tunney before their bout in St. Paul on March 27, 1925. Tunney dominated the fight as Greb was no longer in his prime and Tunney was on his way to the top. Although the one-eyed Greb was arguably the toughest fighter of all time, Jim favored the boxer. Of course, Jim was partial to the Irish, especially since Tunney was arguably the greatest Irish athlete of all time. Jim also liked him because, as Bert Sugar observed, Tunney “drew on the style of that prince of the middleweight division, Mike Gibbons” (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 40).

This photo is one that Jim kept. On the left is the reckless fighter hiding the fact he could see out of only one eye. On the right is the calculating boxer. Who’s between them? Why integrity, Minnesota’s George Barton himself. They say Barton still holds the world record for having refereed over 12,000 amateur and professional bouts. With twenty-seven years to Jim's twenty-five, Barton also is the longest-serving boxing commissioner in Minnesota history, if not all of history.

In large measure, this photo sums up the sport of boxing, with perhaps the puncher Jack Dempsey being the only missing part. When you consider that the year of the photo is 1925, you can almost see the long shadow of Dempsey, then the heavyweight champion of the world. So really you have a fighter, a fair-and-square ref, and a boxer—while the puncher is in the back of everyone’s mind.

Jim also valued the photo for at least two personal reasons. First, the photo is interesting because from the toughest streets of St. Paul through the Ramsey County Home for Boys to the St. Paul Auditorium, Jim was a street fighter who became a boxer. Second, when the photo was taken in St. Paul in March 1925, Tunney’s most ardent fans included some of Jim’s older brothers, and even they couldn’t have imagined that Tunney would take the title away from Jack Dempsey eighteen months later.

At the time of the photo, Greb was the world middleweight champion (160 lbs. max.) and Tunney the American light‑heavyweight champion (175 lbs. max.). Greb is ranked number five, pound for pound, on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time, after only Sugar Ray Robinson, Henry Armstrong, Willie Pep, and Joe Louis. Tunney is ranked number thirteen out of the top one hundred (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 14, 15, 40 and 42). Harry Greb schooled Jack Dempsey when they sparred on a couple of occasions in 1920. See Round 10, entitled “Joe Louis.”

Jim and his wife, Kitty, raised four children. So what did he and Kitty teach their children from boxing and life? Foremost: perseverance and dignity. Learn a skill, whether in boxing or any other endeavor, and then try and have the self-respect to keep trying to execute with integrity. If dignity is self-respect, Jim defined integrity as keeping to the high road.

Some other lessons don’t take a lifetime to learn: Punches need to pop: Jab—Jab—Boom. Jab—Jab—Boom; The chin, at its point, is a “light switch.” When it’s hit the opponent “drops like a sack of potatoes;” Don’t blow your nose! (After taking a shot to the face, your eyes will blacken if you blow your nose); Don’t quit your day job; Never let your guard down. Show no one your back, and be alert for the sucker punch—it could be a Sunday punch.

Jack Dempsey resorted to the undignified sucker punch, which also was the Sunday punch, in September 1920 when he put his title on the line against St. Paul native Billy Miske in Benton Harbor, Michigan. Miske had just gotten up off the canvas, and Dempsey was lurking behind him (Clay Moyle, Billy Miske: The St. Paul Thunderbolt, 124–125 (Win By KO Publications 2011)).

Before he was champ, Dempsey fought Miske at the St. Paul Auditorium in May 1918. Winning by a shade, Dempsey said later that night: “If I ever have to fight another tough guy like that I don’t want the championship. The premium they ask is too much effort” (Clay Moyle, supra, at 54).

Jack Dempsey is ranked number nine on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 26). Miske was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2010.

Dempsey lost the title to Tunney, a ten-round decision, on September 23, 1926, in Philadelphia. When Dempsey unsuccessfully tried to regain the title from Tunney on September 22, 1927, in Chicago, he might have positioned himself to use the undignified sucker punch. But as The Ring magazine points out: “Just so long as Dempsey refused to go to a neutral corner so long did referee [Dave] Barry refuse to start counting [when Tunney was down]” (The Ring, June 1972, at 45).

In the time it took Dempsey to submit to the farthest neutral corner after connecting with his vicious left hook in the seventh round, he'd given Tunney precious extra seconds to rest and clear his head. Tunney is reported variously as having no less than fourteen seconds and as long as eighteen seconds before he stood to beat the official ten count (Id.). Bert Sugar called this long count “perhaps the most famous moment in all of boxing” (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 41). Tunney went on to get the decision in this ten-rounder, and they say Dempsey was gracious in defeat.

Imagine the golden age of boxing: 104,943 fans witnessing the Battle of the Long Count at Soldiers’ Field in Chicago on Thursday September 22, 1927; and even more: 120,757 fans witnessing the shocking upset victory of Tunney over Dempsey at Sesquicentennial Stadium in Philadelphia a year earlier on Thursday September 23, 1926 (The Ring, supra, at 44 and 45). Many of those fans knew a boxer personally or were boxers themselves at some level. In St. Paul, where both Dempsey and Tunney had fought on their way up, Jim’s brother and future mentor John listened for reports on the fights and couldn’t wait to test his own skills.

You can see Tunney dethrone Dempsey, and view Tunney’s footwork despite the rain and wet canvas, at www.genetunney.org. Watch for Tunney’s pops to Dempsey’s face, right-hand leads, early in the first round.

They say the single most difficult thing in sport is to hit a golf ball, and hitting a baseball second. High on the list has got to be Jack Dempsey’s chin. So Tunney can be excused for missing it, especially given that he still connected well. Tunney executed when he saw the opening that he'd anticipated as part of his fight plan. As Dempsey prepared a left hook, pop, pop (Jack Cavanaugh, Tunney: Boxing’s Brainiest Champ and His Upset of the Great Jack Dempsey, Chapter 19 (Ballantine Books 2007), Kindle Edition).

Now that’s the artistry of a boxer: guts and inspiration, training and planning, footwork and execution.

Gene Tunney’s parents, Mike Gibbons’ parents, and Jim’s maternal grandparents all came to the United States from Ireland’s County Mayo. See Round 4, “The O’Hara Name & St. Paul.”

Harry Greb and Gene Tunney before their bout in St. Paul on March 27, 1925

Round 3: The Unspeakable

“The fight for survival,” said Rocky Graziano, “is the fight.” On Thursday July 17, 1947 in Chicago, Graziano knocked out Tony Zale in the sixth for the world middleweight title.

Born a southpaw twenty-two years earlier, Jim O’Hara was placed in an orphanage at six years of age with his older brother Mike and their youngest brother Dick. They were there because their father couldn’t find work and their mother was in St. Paul’s Anchor Hospital with tuberculosis.

In the orphanage, the good nuns made Jim right‑handed. Little did they know that his naturally powerful jab would later surprise many a foe.

From the orphanage, Jim and his siblings eventually returned to the Mount Airy, Rice Street, and East Side neighborhoods of St. Paul, including welfare housing projects. Jim referred to his childhood neighborhoods as the badlands. “The farther you walked, the tougher it got," he said. "We lived in the last house, upstairs.”

Jim and his brother Mike looked out for each other on the streets, literally fighting for their lives. On at least one occasion, they faced each other in the ring in Duluth. When asked if they took it easy on each other, Jim answered with a smile, “We did until the first punch was thrown.”

On Friday October 26, 1951, in New York, a young Rocky Marciano knocked out an old Joe Louis in the eighth in what was the end of Louis’s long career. Mike and Jim, both heavyweights, followed the up-and-coming Marciano with keen interest: Mike the fearsome and fearless street fighter, Jim the scientific boxer.

Tragedy struck eight days later on Saturday evening November 3, 1951. Mike’s body was found in downtown St. Paul’s Jackson Bar on West 6th Street. Jim saw the unspeakable. Mike was only twent-seven at the time of the fatal shooting. The killer had been considered a family friend.

At the time of his death, Mike had a wife and child to support and was looking for full-time work. He’d argued with the killer over a job, and it turned physical. In anger, the killer left and returned with a gun. He then hid at his sister’s house from Mike’s six brothers while contacting the police to be taken into custody. The killer was the president of the St. Paul Bartenders Union of which Mike was a member. Tried and found guilty of manslaughter in the first degree, he was sentenced to ten to twenty years at Stillwater State Prison (“10-20 Year Sentence Given . . . For Mike Ehrich Slaying,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, circa February 1952).

Jim was twenty-five when Mike was killed. He himself had a wife and child and his wife’s grandmother at home to support, and now Mike’s tragic death changed things forever. If the framework for Jim’s mental toughness hadn’t been completely formed, it was now. He faced his brother’s violent death and ultimately concluded you’ve got to forgive to better yourself. “Hate hurts you more than the guy you hate,” said Jim. “He doesn’t care. You need to forgive him for yourself.”

One of Jim’s life lessons was that there’s a time to fight and a time to forgive. Years later, he regularly supervised boxing events within the walls of Stillwater State Prison. As he sat there ringside, he was reminded of the man who’d killed Mike and served his time there.

From Mike’s death, Jim saw reality for what it is. He wasn’t overly impressed with big shots. When told someone was so and so, Jim responded: “Is that right? Tell me, what happens when he gets hit on the chin?”

Jim didn’t prejudge anyone on the basis of race or religious belief. For him, each man stood on his own merit. When he boxed in San Francisco in the winter of 1947–1948, he drove there with another boxer who happened to be black. Later when others spoke of the supposed Good Old Days, Jim responded: “Yeah, right. You mean the days when a man couldn’t eat in a diner if he had the wrong color skin?” He also no doubt thought of the night Mike was killed.

Jim had no time for oppressive people, phonies, or loud mouths. He appreciated those who know what they’re talking about, and he advised that whenever you encounter them, “Shut up and listen because you already know what you know.” By the same token, he didn’t tolerate flattery. “Cut it out,” he’d say.

The same streets that at times could be dark and ugly fostered an appreciation of beauty. One of the guys from the neighborhood was the famous artist LeRoy Neiman, born in St. Paul in 1921, three years before Mike. From his childhood experiences Neiman spoke of the image of a good boxer as a thing of beauty:

I have such great respect for the fighters, which stems from my childhood as a Depression kid growing up in a poor neighborhood in St. Paul, Minnesota. I didn’t like fighting, except with the gloves on. I came to New York in 1960 and started drawing at Madison Square Garden. I’m amazed at every fight, watching these guys walk up the ring steps. I’ve done the good quarterbacks, the home-run hitters, (Alex) Rodriquez at third base. But I don’t know of any athlete who is as beautiful as a good fighter. (Dave Newhouse, Before Boxing Lost Its Punch, Introduction (ebooks 2012).)

Neiman was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2007. He grew up in St. Paul with “basement boxing” at his neighborhood Catholic church. He appears in the films Rocky III (as an artist sketching Balboa and as the ring announcer) and Rocky IV (as the ring announcer). His artwork appears on the screen during the credits at the end of Rocky III.

In his 2012 autobiography, Neiman wrote about growing up around boxing:

Boxing was a way out of the slums for street kids — a hard way to make an easy living, as the saying went — and during the Depression, pugs were invariably recruited from the underprivileged. We looked up to these guys, who were for the most part street hooligans in Everlast mitts. A cauliflower ear in those days was a badge of honor. (LeRoy Neiman, All Told: My Art and Life Among Athletes, Playboys, Bunnies and Provocateurs, Chapter 1 (Lyons Press 2012), Kindle Edition.)

Jim had no illusions about being a contender for the world heavyweight title. He was a scientific boxer who refused to bring his street fighter’s kill-or-get-killed attitude into the ring. He was able to compartmentalize, control himself, and expend energy in installments over a lifetime.

If you knew the intensity he could bring as well as his street smarts, there wasn’t any doubt in your mind. You knew him to be one of the class of men you’d want with you in the event you found yourself facing a no-holds-barred meeting in some back alley. He'd know what to do; he'd learned well how to live by his wits.

He told the story of being a street kid coming up against a foe who gave chase. The guy was older and bigger. After wearing him out running, Jim turned around and took care of business. If fighting is undignified, Jim’s poise made it seem less so.

Thus there was an acquired dignity about Jim O’Hara. He wasn’t impressed if you were known as a good street fighter. He knew the potential cost of trying to get ahead outside the rules. He was impressed and pleased when you distinguished yourself within the rules, including sticking with school and getting a formal education.

Late one evening in 1992, Jim telephoned. He was crying, “Your mother and I watched a movie tonight,” he said. “A River Runs Through It. It's about two brothers. One was just like Mike.”

Life is about people, and the depth of Jim's sorrow was too great for him to say anything more.

Round 4: The O'Hara Name & St. Paul

James John Ehrich, who became known as Jim O’Hara, entered the world on December 23, 1925.

His birth place was St. Paul, Minnesota. Destined to earn a PhD in street smarts from the St. Paul campus of the School of Hard Knocks, he fell in love with the city’s people and places. Among the people were St. Paul’s many sweet scientists, such as his brother John, whom Jim grew up watching at their places of business, which more than on occasion included the streets.

Jim’s mother was named Margaret O’Hara. Born in St. Paul in 1890, she was the daughter of Mary and Joseph O’Hara, Irish Catholic immigrants. They also had a son, John, born in 1892. Dedicated to each other and hardworking, Mary and Joseph were living the American Dream with their own general store at Seven Corners in downtown St. Paul. But when Mary took ill and died, Joseph quit.

Grief stricken, he couldn’t go on.

Mary died Friday March 9, 1894, at ten in the morning at home above the store (Missal of her son John, the inside back cover (to which he pasted his mother’s obituary)).

On Sunday afternoon following the funeral Mass at the Cathedral (then located on the corner of St. Peter and 6th Streets in downtown St. Paul) and the burial service, Joseph directed his two youngsters to go with their Aunt Marge Cummings. Margaret and John never saw their father again.

The cause of Mary O'Hara's death isn't known, but her husband is believed to have returned to County Mayo, Ireland, to live out the rest of his days. How could he live without his children? You'd think he'd care for them, but perhaps in his own way he did.

Mary was only twenty-nine when she passed. Margaret O’Hara, age four, was raised by Aunt Marge. John O’Hara, age two, was legally adopted by Ellen and Thomas Hoban and became their only child, John Hoban (Missal of John Hoban, the inside back cover (to which he pasted the notice of his adoption)).

Jim’s mother was born into and grew up among the boxing Irish. In the year she was born, 1890, Irish Americans held five of the world titles out of then seven weight divisions (Jack Cavanaugh, Tunney: Boxing’s Brainiest Champ and His Upset of the Great Jack Dempsey, Chapter 1 (Ballantine Books 2007), Kindle Edition). Her folks were from Ireland’s County Mayo, as were the parents of Mike and Tommy Gibbons. The Gibbons brothers were born in St. Paul about the same time as she: Mike, 1887; Tommy, 1891. Both are members of the International Boxing Hall of Fame. A middleweight, Mike was inducted in 1992; a light-heavyweight, Tommy was inducted in 1993.

The Gibbons brothers are ranked number three on the list of Boxing’s Best Brother Combinations, a list Steve Farhood put together (Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas, The Ultimate Book of Boxing Lists, 78 (Running Press 2010)). World-class boxer Jack Gibbons, Mike’s son, was born in St. Paul in 1912.

Arguably the greatest Irish athlete of all time is Gene Tunney. His folks also were from County Mayo. Born in New York City in 1897, Tunney is ranked number thirteen on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time. Mike Gibbons is ranked number ninety-two out of the top one hundred (Bert Randolph Sugar, Boxing’s Greatest Fighters, 29 and 314 (The Lyons Press 2006)).

Mike Gibbons is ranked number five on the list of the top defensive fighters of all time, a list Bert Sugar put together, while Tunney is ranked number eight on the same list (Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas, supra, at 162).

Jim’s father’s name was Ehrich, Herman Ehrich, pronounced in the family “Eric.” Born in Iowa in 1881, Herman is believed to be the son of German immigrants.

“I’m half Irish and half smart,” Jim would say.

A close friend of the owners of Schmidt Brewery in St. Paul, Herman had at one time run a team of horses delivering product for the company. When Jim later asked his father why he never became an owner of the company like his German buddies, his father replied, “The sauce,” by which he meant alcohol.

Jim’s quip about being half Irish and half smart was his spin on Billy Conn’s famous line, which Conn delivered after his 1941 loss to Joe Louis: “What’s the sense of being Irish if you can’t be dumb?” Conn had the heavyweight champion of the world beat on points after twelve rounds. All Conn had to do was stay away from Louis, but instead he got cocky and started trading punches with the champ. Louis won by KO (Randy Roberts, Joe Louis: Hard Times Man, Chapter 7 (Yale University Press 2010), Kindle Edition). Conn’s remark has to be, and is, on the list of the best post-fight lines (Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas, supra, at 205).

Neither Gaelic nor German was passed down in the family. But Jim was known to say “Bist du verruckt?” That’s German for “Are you crazy?”

He developed a big heart from a big family. The arranged marriage of his parents circa 1907 produced twelve children—seven boys and five girls. His parents named their daughters: Mary, Ruth, Ann, Lorraine, and Joan; and their sons: Edward, William, John, Robert, Michael, James, and Richard. Jim was the tenth of the twelve children and the sixth of the seven boys.

At some point before Jim was born, and perhaps during his earliest years, his parents owned a farm near the north end of Rice Street in St. Paul. From the farm come the stories of Jim’s father military pressing a small horse and, on another occasion, knocking out a horse with a single punch.

Eventually their home on the farm was lost to fire. The family then began an odyssey of moves within the city’s rough inner-city neighborhoods, including public housing near the south end of Rice Street.

During some of the Great Depression, Jim and his brothers Mike and Dick resided in an orphanage where Jim was required to become right-handed. Known as St. Joe’s and run by Benedictine nuns, the orphanage had a south Minneapolis location as well as a St. Paul location.

Six years of age, Jim arrived at St. Joe’s in south Minneapolis in February 1932 and remained there until March 1933. Jim called his father "Pa," and years later he forgave Pa for never coming to visit, what with twelve children and Jim’s mother in St. Paul’s Anchor Hospital with tuberculosis and the difficulty of finding work during the Great Depression.

The good Sisters of St. Benedict did their best at St. Joe’s, but life was hard there, as it was all over. Don Boxmeyer, writing for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, wrote in 1994:

More than 3,500 children would live at "St. Joe’s" [in St. Paul] in an era when the orphanage was the only refuge for children from bad, broken or no homes.

Many non-Catholic children lived there over a period of years and many children who were not even orphans. There were children whose mothers were sick with TB, with cancer, and whose fathers could not care for them.

***

Everyone’s birthday was celebrated on the same day, and there’d be a cupcake on each dinner plate along with one nickel.

***

[In St. Paul] the boys’ dormitory was in the attic, or the fifth floor, in a space that was bleak and barren. During thunderstorms, the sisters would get the boys out of bed and have them kneel in a circle around a lighted candle to pray the Rosary, which was an unforgettable experience, some children recalled. And the sisters, ever frugal, would keep the wax that dripped from the candles, melt it, and the children would use it to wax the floors.

***

The sister orphanage in south Minneapolis operated much the same way. . . .

When the [Minneapolis] orphanage’s chickens were laying, the kids each got one Sunday morning egg, hard-boiled. But usually the morning meal was "mush," Pat [Marcogliese] recalls. "The nuns would lick you if you didn’t eat the mush, but I couldn’t eat it and wouldn’t eat it, so I got licked. Finally, they got tired of licking me and let me alone. I was a terrible kid, just awful, and I deserved every single licking I got."

The routine was much the same in St. Paul, Paul [Gonzalez] says. Oatmeal (into which was mixed cod liver oil) for breakfast all year long, and maybe once or twice a year the kids got an egg. (“Bless Our Home/St. Joseph’s Orphanage, Run by Benedictine Nuns For More Than 100 Years, Finally Closed Its Doors In The 1960s. But Those Who Grew Up There Remember It well,” July 16, 1994, Express Section, page 1D.)

Jim didn’t like to talk about the dark days in his life, but he did mention they each got an orange on Christmas morning.

He and his siblings returned home as soon as their mother’s health allowed. For two years, she was in St. Paul’s Anchor Hospital with TB. During this period, Joanie, the youngest child, was taken in by big sister Ruth.

Jim’s mother’s brother, John Hoban (O’Hara by birth), served in World War I and thereafter had a good job in St. Paul with American Linen. By the time he retired, he held the office of credit manager. He and Jim both had a gift with numbers. See Round 12, entitled “Education.”

Uncle John and his wife, Ethel, gave their nephew Jim special treatment. In March 1933, when Jim was seven, they took him into their home, reducing the length of his stay in the orphanage. The only known photo of Jim as a child is in the backyard of the Hoban house where he is seen having fun with his cousin Tom, age six, in the summer of 1933.

Uncle John and Aunt Ethel also were generous with financial support to Jim’s mother. As part of his big family, Uncle John and Aunt Ethel were part of why Jim developed a big heart.

While his sister had twelve children, Hoban had one child, Tom, and he was about Jim’s age. In 1942–1943 when Tom was a junior in high school, he caught up with Jim once a week for boxing lessons. Uncle John had initially set up the lessons with Jim, wanting Tom to learn the art of self-defense. Jim was then an amateur boxer, training each weekday in the famous (if modest) Mike Gibbons Rose Room Gym in the basement of the Hamm Building in downtown St. Paul. He arranged for the use of the ring whenever his cousin Tom came over from West St. Paul.

At age sixteen, Jim had moved out and was supporting himself. He made it a point to bring his mother whatever he could, such as hams and turkeys, including some from the generosity of his pal Bert Sandberg, whose family was in better shape financially.

About this time, Jim was playing baseball with his buddies when he experienced pain in his feet. It was found to be the gout, a form of arthritis. It wasn’t altogether a shock because from an early age his older sister Ruth suffered with rheumatoid arthritis, which eventually crippled her.

From the gout attacks, Jim didn’t get the opportunity to serve his country in World War II. He was embarrassed to be rejected from the United States Army and classified 4‑F. If there was shame in being poor, wearing civilian clothes when everyone else was in uniform only added to the Irish chip on his shoulder. The gout interfered with his boxing from time to time, with the pain adding to his toughness.

Rocky Graziano was born in New York City in 1922, three years before Jim. Dishonorably discharged from the army for going AWOL one too many times, Graziano was spending time during the war with Norma, his future wife, when his civilian clothes attracted attention:

While walking in Greenwich Village, three sailors baited Rocky, saying he was 4-F. They called him a "fairy" and added that he dressed like a girl.

Rocky instructed Norma to "Wait right here, honey." He whirled and dropped two of the sailors with body shots while the third ran away. Norma worried that Rocky had taken liberties as a professional fighter, until he explained to her that is exactly why he didn’t hit them in the head. (Dave Newhouse, Before Boxing Lost Its Punch, Round 2 (ebooks 2012).)

Graziano is ranked number ninety-eight on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 336).

Stomach cancer took Jim’s mother in 1945 when he was nineteen. In June 1945, in what may have been his second recorded professional fight, Jim was knocked out in the first round as a welcome to the pro ranks. He boxed under the name Jimmy O’Hara, following the lead of his older brother and mentor Johnny O’Hara.

From being forced by the good nuns in the orphanage to become right-handed to living on his own at sixteen to gout attacks, the 4-F stigma, his mother’s death, and now the life of a boxer, nothing was easy. From challenges including unspeakable loss and alcoholism, he was to have a lifelong compassion for the weaknesses and sufferings of others.

If he was ever tempted to think of himself as tough, he remembered those who'd gone off to war. While he was enjoying three square meals in St. Paul, tougher Americans like First Lieutenant Louis Zamperini of Torrance, California, were being severely beaten and starved in Japan. A member of the 1936 US Olympic team, Zamperini had run a 4:12 mile on the sand of Oahu the morning of the day his plane went down over the Pacific (Laura Hillenbrand, Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption, Chapter 11 (Random House 2010), Kindle Edition).

A source of pride for Jim was his brother Bobby Ehrich who served in the US Marine Corps. A driver of one of the landing crafts at the Battle of Iwo Jima, Bobby did his part in the eventual US victory in the Pacific. There’s a photograph of him and some buddies in the Pacific holding up a captured Japanese flag. Bobby had a full head of hair in the photo, but from all the things he survived, he returned home practically bald.

When Jim married in 1948, he changed his name legally from Ehrich to O’Hara with his father’s blessing. While he had two family names, he answered to many other names throughout his life, including Seamus, Irish, James J, Handsome Jim, and Jumbo Jim or Jumbo.

At six foot one, he had a big frame with a large torso. His professional boxing weight was 200 pounds. Later in life, he gained weight, maybe topping off at 250. He was solid. You’d never call him fat. In the 1970s, he was dubbed "Jumbo" Jim O’Hara by Don Riley, sports columnist for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, after the Boeing 747 Jumbo Jet became popular. The name Jumbo stuck among Jim’s children and their friends.

To those who confided in him, he was known as Jimmy Never-Tell, as he himself put it.

Strong as they come, Herman Ehrich, Jim’s father, lived and worked to age ninety-six. No nursing home for him; he was always able to care for himself. He kept his mind sharp with baseball stats and listening to sports broadcasts on the radio. At the time of his death in 1977, his apartment was above the St. Paul Barber School (on the corner of University Avenue and Rice Street in St. Paul), where he made pocket money each day sweeping up hair. Without teeth for decades, he enjoyed raw hamburger. Whether or not it’s true that tough guys eat raw meat, Herr Ehrich was tough.

With a population of over three hundred thousand in 1950, when Jim was in his prime, St. Paul is the last city in the East before you hit the Mississippi River. Full of character, its streets are a UPS driver’s nightmare, at least before the days of GPS. You won’t find a grid-numbering system applied to the streets of this town in east-central Minnesota.

Back in the day, a GPS would have been nice, but growing up in St. Paul, you naturally learned how to get around, using roadways named Ford, Snelling, St. Clair, Lexington, Selby, Dale, Maryland, White Bear, Shepard, and Warner, among others.

Downtown St. Paul is built along the banks of the Mississippi. Summit Avenue mansions look out over downtown, indeed to Jim’s grandparents’ building on Seven Corners, and then on to the river.

They say F. Scott Fitzgerald, born in St. Paul in 1896, lived on Summit Avenue and had in his mind’s eye a great estate near the intersection of Mississippi Boulevard and St. Clair Avenue when we wrote The Great Gatsby. Fitzgerald attended St. Paul Academy from 1908 to 1911 before leaving for East Coast schools.

The majestic St. Paul Cathedral and the State Capitol, a smaller version of the US Capitol, also look out over downtown and the Mississippi.

Commercial activity has long been aplenty, with the likes of 3M, which investor Lucius Ordway moved to St. Paul from Duluth in 1910. (The birthplace of singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, Duluth also is one of Minnesota’s largest cities.)

St. Paul’s Ecolab began in 1923 as Economics Laboratory. In 1853, St. Paul Companies was founded as the St. Paul Fire and Marine Insurance Co., and as of 2003, it’s known as St. Paul Travelers.

With German, Irish, French, Scandinavian, Polish, Italian, and Mexican immigrants, Gentiles and Jews and their descendants everywhere when Jim was a boy, St. Paul couldn’t help but capture his heart and imagination. The Irish were the cops and the politicians as well as the boxers, which is why his brother John used the O’Hara name in the ring, and Jim followed suit. See Round 6, entitled “The Boxer.”

Jim grew up amidst police corruption and criminals finding sanctuary in St. Paul under O’Connor’s Law, a decades-old system of bribes and payoffs. Paying for protection as they went to and fro, the criminals were open and notorious. John Dillinger, Machine Gun Kelly, Baby Face Nelson, Ma Barker and her sons, including Doc Barker, were known to frequent St. Paul, including its many illegal saloons and gambling establishments.

When alcohol was illegal (1920–1933), they say O’Connor’s Law became a conspiracy among St. Paul’s German breweries and St. Paul’s Irish cops and politicians. As a German-Irish street kid, Jim witnessed his share of corruption. His brother John was a professional fighter during these formative years for Jim (1929–1934), and Jim observed you needed to pick your battles, sidestep certain people, and always show respect to those in authority.

O’Connor’s Law welcomed criminals to St. Paul as long as they committed no violent crimes or robberies within city limits. Named after John J. O’Connor, the St. Paul Police Chief who began the rule long before Jim was born, this system continued until it was closed down for good by wiretaps of police headquarters in 1935. Of the many in law enforcement and politics who helped put an end to the corruption, one was boxing Hall of Famer Tommy Gibbons himself.

Fearless of what lay ahead of him, Gibbons ran for office and was elected sheriff of Ramsey County in 1934. St. Paul is part of Ramsey County.

As mentioned, one of the bad guys was Doc Barker, who never knew a jail he couldn’t break out of—until he met Sheriff Gibbons. The sheriff was holding Barker pending the Feds taking custody of him when Barker asked for his own bathtub in his cell. Gibbons denied the request but not before asking why a bathtub. In an interview in 1959, he explained:

The strange request aroused my curiosity so I visited Barker. As I approached his cell I noticed Doc going through a strenuous session of calisthenics which Bob [the guard, Mike Gibbon’s son] explained to me was a regular routine several times daily. Asked why he should be provided with a bathtub, a privilege denied all prisoners, Barker replied:

"I’m keeping in tiptop shape, Sheriff, and you know after working up a good sweat, a fellow needs a bath. I know I’m going to be sent to Alcatraz and I know I’ll have to be in top condition to swim the bay from the Rock to Frisco after I make my escape. If you are a betting man, Sheriff, lay a few bucks on my making good."

Needless to say, I didn’t furnish Barker’s cell with a bathtub, but he did break out of Alcatraz only to be shot to death in the water as he started to swim the bay. (George A. Barton, “Tommy Gibbons, Part III”, The Ring, December 1959, 18, 19, and 57.)

Hot and humid in the summer and fall, St. Paul has a unique range of temperatures. Back in the day, boxers trained in the heat and humidity without air conditioning. In the fall of 1953, notably, Jim’s effort paid off with a unanimous decision over slugger Don Jasper in Duluth with the thermometer at one hundred degrees Fahrenheit ringside. See Round 7, entitled “Boxing Record.” Imagine the temperature in the roped square.

Freezing cold in the winter, St. Paul answers the low temperatures after the holidays with a winter carnival, which warms you with its annual parade and treasure hunt among other activities. Jim’s kids grew up participating in the St. Paul Winter Carnival parade, riding in the horse-drawn carriage owned by his customer the JR Ranch of Hudson, Wisconsin. See Round 13, entitled “The Businessman.”

Winter can be long in St. Paul. There can be snow still on the ground on the 17th of March, St. Paddy’s Day. In 1967, Jim was a member of the booster group that launched the annual St. Patrick’s Day Parade. His participation was only natural. With the O’Hara name and people skills ordinarily reserved for kissers of the Blarney Stone, he hung out at the saloon belonging to Bob Gallivan, the visionary for the event.

Gallivan’s Bar & Restaurant, located on Wabasha Street in downtown St. Paul, was one of the venues where Jim came to know many lawyers and judges and politicians. The location was near both the court house and city hall building and the St. Paul Pioneer Press Building.

With a smaller city feel, St. Paul is part of a large metropolitan area. You can’t describe St. Paul fully without mentioning Minneapolis, the city of lakes, which would be contiguous if the river didn’t divide the two cities. Minneapolis is immediately west across the Mississippi. One of many bridges between the cities is the Ford Bridge, officially the Intercity Bridge, which takes you high above the river to Minnehaha Park. There you can see and hear Minnehaha Falls and follow the trails to the Mississippi where you can fish for smallmouth bass and walleye.

If Minneapolis is the city of lakes, you might say St. Paul is the contender in the world of sports. Before turning to St. Paul’s athletes, Minneapolis of course can hold its own. Indeed you can thank Minneapolis for the name “Golden Gloves,” which originated in the 1920s with Minneapolis's Nick Kahler of hockey fame.

Inducted into the US Hockey Hall of Fame in 1980, Kahler needed money back in the 1920s to fund a hockey team. He recognized that amateur boxing tournaments would be the ticket. He named them “Diamond Belt” tournaments. At that time, a boxing program couldn’t get far in Minneapolis without the blessing of its adopted son Jimmy Potts, who’d fought nearly one hundred pro matches in his day, not to mention his pro wrestling matches. Jimmy along with his brother Billy became the proprietors of the famous Potts Gym downtown at the intersection of Hennepin Avenue and 6th Street.

Upon meeting the Grand Old Man of the Ring, as Jimmy Potts was known, Kahler noticed Potts had tiny gold boxing gloves attached to his watchband. Kahler was able to borrow those tiny gloves and had inexpensive replicas made to give out as awards at his fundraising tournaments. Later he met sportswriter Arch Ward of Chicago who asked Kahler’s permission to use the tiny gloves as a symbol for Ward’s amateur tournament in Chicago. He said to Kahler, “Nick, you got to let me use these as a symbol of our tournament. We’ll call it Golden Gloves.” They say the author Paul Gallico came up with the same name for his amateur tournament in New York about the same time (Les Sellnow, They Came to Fight: The Story of Upper Midwest Golden Gloves, 9–11 (Bang Printing 2013)).

Back to St. Paul.

There’s no question boxing put St. Paul on the map. You have undefeated Charley Kemmick crowned welterweight champion of America in 1891; Johnny Ertle, bantamweight world champion, 1915; Mike O’Dowd, middleweight world champion, 1917; Lee Savold crowned world heavyweight champion by the British Boxing Board in 1950; Mike Evgen, light-welterweight world champion, 1992; and Will Grigsby, light-flyweight world champion, 1998.

Minnesota’s most famous boxers are St. Paul’s brother combinations Mike and Tommy Gibbons from their work in the 1910s and 1920s and Del and Glen Flanagan from the 1940s and 1950s.

Then you have heavyweight contender Billy Miske in the 1910s and 1920s; light-heavyweight contender Jimmy Delaney in the 1920s; light-heavyweight contender Jack Gibbons (Mike’s son) in the 1930s; middleweight contender Jock Malone in the 1920s and 1930s; light-middleweight contender Gary Holmgren in the 1970s and 1980s; and light-middleweight contender Brian Brunette in the 1980s.

These legends and others are highlighted throughout Jim’s story, particularly Round 6, entitled “The Boxer;” Round 8, entitled “Honors & Awards;” and Round 14, entitled “The Storyteller.”

St. Paulites famously hit baseballs too. Big league Hall of Famers Dave Winfield and Paul Molitor developed their skills growing up in St. Paul in the 1960s and 1970s. Winfield got his start at Oxford playground with no-nonsense Bill Peterson coaching and Molitor at both Linwood and Oxford playgrounds with various coaches, including Dennis Denning and Wally Westcott as well as Peterson. Peterson also later coached Molitor’s high school team. If you rarely saw Molitor in person after he graduated to the pros, you’d be hard pressed to name a more likable grade-school-through-high-school classmate.

Each decade, every city produces its great, multisport athletes. In the 1970s in St. Paul, there were others you thought stood out as much as Molitor if not Winfield, and not just the ones who became big names like Jack Morris. They were names of raw athleticism like:

Steve Winfield, known for his play in baseball, older brother to Dave Winfield;

Sean Flood, football;

Mike Maki, football and baseball;

Tom Eha, football and hockey;

Mike Gartland, football;