Middle Rounds

Round 6: The Boxer: Part I

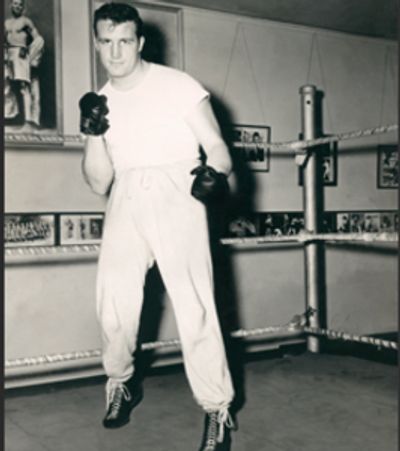

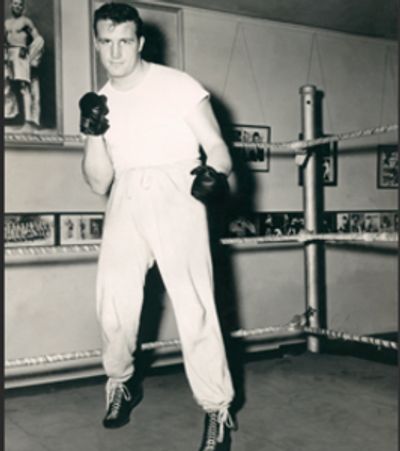

There's a photo of Jim O'Hara striking a pose in his sweats and bag gloves at Weller's Gym circa 1947. He's alone in the ring, on his toes, his left foot forward. His shoulders, neck, and head suggest the slip of a right hand. His left is held low, drawing the right and setting up the counter. His right is pointed up, the arm folded at the elbow, guarding the liver.

Don Riley, the famous sportswriter, described Jim thusly:

He was a big guy but a boxer. He wasn’t a big hitter, and he carried his hands low, like the great fighter from Pittsburgh, Billy Conn, the way Muhammad Ali later did. We always kidded him about his Pittsburgh style. (See the Foreword by Jim Wells, supra.)

If Jim had no illusions about being a contender at the highest level, and if he wasn't concerned about getting credit in the history books for all his matchups, he had science. He was a boxer. And he was a boxer during the golden age of boxing.

Some debate whether those in the fight game today can compare with those back in the golden age of boxing. One thing is certain, back in the day, you had more competition with and proximity to the greats, like Mike Gibbons, who became teachers of boxing.

So what is boxing? Teddy Atlas has put it this way:

Boxing means using your head, using geometry, using the science of angles, the science of adjustments. And all you have to do is make it a kind of landscape where the other guy can't use what he has. You fight in a place where speed doesn't come into play. You use your reach to keep your opponent at a certain distance where you can time him. Timing can always get the better of speed when it's used properly and understood properly. You time your opponent and keep him at the end of your punches. And if you use your reach properly you are not giving him anything to counter. (Mike Silver, The Arc of Boxing: The Rise and Decline of the Sweet Science (McFarland & Company, Inc. 2008), which includes remarks by Teddy Atlas, Kindle Edition.)

“The biggest steps you’ll ever climb,” Jim cautioned many times, “are the three into the ring.” Every opponent is dangerous. The fight game takes guts but, more importantly, the ability to think on your feet.

Jim spent more than a decade thinking on his feet, 1941 through 1953. At six foot one and 200 lbs., he was a heavyweight as a professional fighter. When he was an amateur, he fought as a light‑heavy, not over 175 lbs., and he felt his timing was better with less weight.

They say you need to start young to be a good boxer. By necessity given the neighborhoods of his youth, Jim learned to defend himself at an early age. His pa and five older brothers showed him what fists can do, and there was plenty of opportunity for practice. He also had a tough younger brother to teach. At least one older brother, Johnny O'Hara, fought for pay. See Round 5, entitled “Ronald Reagan.”

A turning point was when Jim put the gloves on under adult supervision at the Ramsey County Home for Boys, now known as Boys Totem Town, in St. Paul, Minnesota. He was about fifteen, and he then began to develop from a fighter into a boxer.

His career officially started in the St. Paul Golden Gloves. Throughout his life, the Golden Gloves would hold a special place in his heart for one main reason: it provides a unique opportunity for young people of all shapes and sizes to challenge themselves. He explained thusly:

Boxing's an individual sport. You're on your own. You know there's three steps up into that ring. It's very challenging to go up them three steps. And when you go up there, you're all by yourself. You got your father, you got your coach, or you got anybody else in that corner. But when that bell rings you go out into that center of the ring and you're there all alone. Any kid who does that, I admire him for it. Whether he wins or he loses, he went up those three steps and he tried it. (Recording of Jim O'Hara played at the Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame Induction Banquet, October 3, 2014.)

The venue where Jim began to challenge himself was the Mike Gibbons Rose Room Gym in the basement of the Hamm Building in downtown St. Paul. It was 1941, the year before George Barton was appointed by Governor Harold Stassen to head the State Athletic Commission, which then regulated boxing.

Thus Jim had the good fortune of getting into the sport when the man of integrity himself, George Barton, was about to be given the authority to look out for belters. Jim would become a successor to Barton thirty-five years later when named executive secretary of the Minnesota Boxing Board. See Round 1, entitled “The Boxing Board.” Jim would serve in the office for twenty-five years, second only to Barton's twenty-seven years of service.

Two numbers in the preceding paragraph equal Jim's sixty years in boxing—his thirty-five years immediately prior to his appointment to the Boxing Board plus his twenty-five years on the Boxing Board.

If modest, the Mike Gibbons Rose Room Gym was knockdown famous. Boxers are accustomed to the smell of their own gyms, and here all the sweat had a glorious history. Indeed, you could say Jim had a boxing pedigree thanks to the Rose Room. So many interesting characters in the field of fisticuffs were associated with the place. If you had to pick a dozen representatives, you couldn’t go wrong with the following:

• Mike Gibbons, middleweight (160 lbs. max.), last recorded fight 1922, inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame 1992. Gibbons is ranked number five on the list of the top defensive fighters of all time and number ten on the list of the greatest Irish-American fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas, The Ultimate Book of Boxing Lists, 162 and 143 (Running Press 2010)). Gibbons also is ranked number ninety-two on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar, Boxing’s Greatest Fighters, 314 (The Lyons Press 2006)). Gibbons was never knocked out in 133 recorded professional bouts. His record is 113 wins (38 by KO), 9 losses, 9 draws, and 2 no contests, including newspaper decisions. A newspaper decision is a bout left in the hands of the sportswriters. Amid the matchmaking that is the business side of pro boxing, Gibbons never got a shot at the world title when he was in his prime. He was so great, fighters avoided him. If his management had been able to pull a Doc Kearns, you’d didn’t have to ask Jim or anyone familiar with Mike Gibbons what the likely outcome would've been. As Jack Dempsey’s manager, Jack “Doc” Kearns got Dempsey his shot. Jim advised never to underestimate the importance of management.

• Tommy Gibbons, light-heavyweight, last recorded fight 1925, inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame 1993. As famous as his brother Mike, Tommy Gibbons’ only losses were to Jack Dempsey, Gene Tunney, Harry Greb, and Billy Miske. You read that right. His only losses were to those fellow Hall of Famers. He was never kayoed until his last fight and then by Tunney in his prime. In all, Tommy Gibbons had 106 recorded professional bouts with 96 wins (48 by KO), 5 losses, 4 draws, and 1 no contest, including newspaper decisions. Tommy and Mike Gibbons are ranked number three on the list of Boxing’s Best Brother Combinations, a list Steve Farhood put together (Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas, supra, at 78). Nat Fleischer was the founder and longtime editor and publisher of The Ring magazine. Born in 1887, he died in 1972 and witnessed perhaps as many fights as anyone in between. He ranked Tommy Gibbons number eight on his list of the top ten all-time light-heavyweights and Mike Gibbons number nine on his list of the top ten all-time middleweights (The Ring Boxing Encyclopedia and Record Book, 10 (The Ring Book Shop 1979)).

• Billy Miske, heavyweight, last recorded fight 1923, inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame 2010. Miske had 105 recorded professional bouts with 74 wins (34 by KO), 13 losses, 16 draws, 1 no contest, and 1 no decision, including newspaper decisions. Clay Moyle’s book Billy Miske: The St. Paul Thunderbolt (Win By KO Publications 2011) is a great read. At page 54, Moyle quotes Jack Dempsey: “If I ever have to fight another tough guy like that I don’t want the championship. The premium they ask is too much effort.” Dempsey was talking about Miske after their May 1918 fight at the St. Paul Auditorium. They say a major motion picture based on Miske’s life and death is in the works. A compelling hero, Miske succumbed to kidney disease at age twenty-nine on New Year’s Day 1924, just fifty-five days after his last fight. A moving novel about Miske came out in 2013, The Final Round, by screenwriter Gary Allison. It’s available on Kindle and in paperback.

• Mike O’Dowd, middleweight champion of the world, 1917–1920, last recorded fight 1923. They say he was the only world champion to fight at the front during World War I. After the war in 1919, he successfully defended his title against none other than Mike Gibbons at the St. Paul Auditorium. It was a so-called no decision bout back then in which Gibbons needed to knockout O’Dowd in order to win. The decision of the newspaper writers of the day also gave O’Dowd the verdict. In all, O’Dowd had 117 recorded professional bouts with 94 wins (39 by KO), 17 losses, 5 draws, and 1 no contest, including newspaper decisions.

• Johnny Ertle, bantamweight champion of the world (118 lbs. max.), 1915–1918 , Minnesota’s first world champion, last recorded fight 1924. Ertle had 88 recorded professional bouts with 62 wins (15 by KO), 20 losses, and 6 draws, including newspaper decisions. At four foot eleven, Ertle could deliver the body shots of a world champion.

• Jimmy Delaney, light-heavyweight, last recorded fight 1927, a world-class fighter. Boxrec.com records 77 of Delaney’s professional fights. His record is reported as 54 wins (21 by KO), 13 losses, and 10 draws, including newspaper decisions. Of his 13 losses, 2 were to Gene Tunney and 3 to Harry Greb. Tragically, Delaney died of blood poisoning in March 1927 at age twenty-six from a cut on his elbow gotten in his recent win over Maxie Rosenbloom. Rosenbloom would go on to become world light-heavyweight king. Born in June 1900, Delaney is reported to have begun training at the Rose Room at age sixteen (The Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame website, 2013). Imagine what heights Delaney could've reached. Heavyweight champion of the world? Another St. Paul legend cut down in his prime is the undefeated welterweight Charley Kemmick, welterweight champion of America (147 lbs. max.), 1891–1895. With 24 wins and no losses, Kemmick died of tuberculosis in 1895 at the age of twenty-three. In a 1928 article, George Barton wrote that some believed Kemmick to be the greatest fighter ever to come from the Twin Cities of St. Paul-Minneapolis. Tommy Ryan, the welterweight champion of the world, refused to fight Kemmick (The Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame website, 2013).

• Jock Malone, middleweight, last recorded fight 1931, a world-class fighter. Malone had 180 recorded professional bouts with 127 wins (34 by KO), 41 losses, and 12 draws, including newspaper decisions.

• Johnny O’Hara, middleweight, last recorded fight 1934, Jim’s mentor and one of his six brothers. John was a member of the class of good, respectable sweet scientists training out of the Rose Room. He exchanged punches with Ronald Reagan. See Round 5, entitled “Ronald Reagan.” On at least one occasion, John boxed under the alias Jackie Ryan, April 10, 1930, in Mason City, Iowa. Boxrec.com records 31 of John’s professional fights—18 wins (eight by KO) and 3 draws against 11 losses, including newspaper decisions. He was fortunate to have learned to box from Mike Gibbons himself, Minnesota’s most famous pugilist. If John never became a contender for the world middleweight crown, he faced at least one in Canadian Frank Battaglia. Jim was an impressionable eight years of age when John was stopped in the second by Battaglia in February 1934 in Minneapolis. A year earlier, Battaglia had fought for the world middleweight title at the Garden (Madison Square Garden). He’d lost to Ben Jeby by TKO in the twelfth. Battaglia would fight again for the world middleweight crown in May 1937 in Seattle. He’d lose this effort to Freddie Steele, who won by knockout in the third. Retiring with a cauliflowered left ear as proof of his orthodox glory days, John had had a near-perfect record of 12 wins and only 1 loss (not to mention 3 draws) when he faced undefeated Glen Allen. They met on June 24, 1930, in Allen’s hometown of Atlantic, Iowa. Allen got the newspaper decision after this ten-round battle, and the two repeated with the same result six months later in Des Moines. Allen retired in 1932 with a 37-6-5 record, including newspaper decisions.

• Jack Gibbons, middleweight and light-heavyweight, last recorded fight 1937, son of Mike Gibbons. A masterful boxer, Jack Gibbons decisioned future middleweight world champion Tony Zale in a December 1934 ten-rounder in Chicago. Zale is ranked number seventy on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 237). Gibbons had 74 recorded professional bouts with 68 wins (20 by KO), 5 losses, and 1 draw, including newspaper decisions. His world rankings are said to have included number four as a middleweight in 1935–36 and number six as a light‑heavyweight in 1936–37. Gibbons was an all-around great athlete. “He was a natural at just about anything he tried,” said Jim. “But more than that, he was just a wonderful person” (Jim is quoted by Jim Wells, “Jack Gibbons Dies At Age 86,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, February 5, 1999).

• Ray Temple, Jim’s trainer and mentor. Jim always credited Temple with teaching him how to box—not how to fight or punch so much as how to move smoothly and box. An accomplished sweet scientist (lightweight, 135 lbs. max.), Temple became a referee as well as a trainer. His last recorded fight was in 1924. Boxrec.com records 39 of his professional fights. His record is reported as 21 wins (5 by KO), 10 losses, and 8 draws, including newspaper decisions. Temple’s birth name was Henry Thoemki.

• Murray McLean, Jim’s manager/trainer and mentor. This man of integrity knew and loved the fight game as much as anyone. He gave Jim his boxing library as well as perhaps the last remaining copy of his work entitled Boxers of St. Paul in which the names of 106 fighters from St. Paul’s past were artfully lettered by McLean. A walking encyclopedia on all things boxing, McLean could tell you the stories of these men and more like no one else. Their names are listed at the end of Round 8, entitled “Honors & Awards.” McLean always had kind words to say about Jim, like those quoted near the beginning of Round 7, entitled “Boxing Record.” “He believed in Jim,” recalled Jim's wife, Kitty, in 2013. “Murray really thought Jim could box.”

• Billy Colbert, matchmaker, promoter, and mentor to Jim. Colbert also managed the Rose Room for Mike Gibbons until the gym closed circa 1949. Recalling a good laugh, Jim credited Colbert with the line that as a promoter “he didn’t mind digging up fighters for his headliners from the Mission House but he’d be damned if he’d go into the graveyards.” In 2013, Peggy Allie, Colbert’s daughter, said she can still see her father and Jim standing together on St. Peter Street in front of the Hamm Building, the location of the gym. It was the late 1940s, and she was in high school at St. Paul’s Mechanic Arts. “They were always joking around together,” she recalled. “Don’t jump,” they said as people peered out the windows of the upper floors of the Hamm Building. From at least 1951 through 1954, Colbert wrote a monthly column entitled “Minnesota Ring News” for The Ring magazine, Colbert’s son, Bill, recalled in 2013. “When I was in the Navy I read his column every month,” said Bill. His father had taken the column over from Spike McCarthy, an equally dedicated boxing man.

Hailing from St. Paul, the renowned artist LeRoy Neiman wrote of Mike Gibbons: “He owned Gibbons Gym (formerly the Rose Room for its long-faded floral wallpaper), a dreary no-frills center of serious sweat, sparring, slugging, and other arts and bruises of the sweet science” (LeRoy Neiman, All Told: My Art and Life Among Athletes, Playboys, Bunnies and Provocateurs, Chapter 1 (Lyons Press 2012), Kindle Edition).

The Mike Gibbons Rose Room Gym closed circa 1949, whereupon Jim completed his move from the longtime home of legends to Weller’s Gym. This new venue was above the Dutchman Bar on Robert Street about a block and a half north of Kellogg Boulevard in downtown St. Paul. The proprietor, Emmett Weller, had opened in 1947 or 1948, and in 1953 Jim would retire from this location. In 1954 Weller moved down the street, and then to three other locations, finally closing his last location (685 Selby Avenue) in 1968.

Weller’s Gym became famous with the likes of the Flanagan brothers and others including Don Weller and Jack Raleigh:

• Del Flanagan, welterweight and middleweight, last recorded fight 1964, inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame 2003. Del had 130 recorded professional bouts with 105 wins (38 by KO), 22 losses, 2 draws, and 1 no contest. “At 145, there wasn’t a fighter in the world who could stay with Del Flanagan,” said Jim, “but by the time he was getting his best shot he couldn’t make that weight.” (Patrick Reusse, “The Fighting Flanagan Brothers,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, Sunday February 13, 2000.) In June 1958, Virgil Akins became welterweight champion of the world. Three months later, Flanagan beat him, a unanimous decision in a nontitle ten-rounder at the St. Paul Auditorium. Akins weighed in at 148 lbs. to Flanagan’s 149 and 3/4 lbs. In his prime, Del Flanagan was so great that fighters avoided him just as fighters had avoided Mike Gibbons. “Del was . . . smooth,” added Jim. “He would come in, throw a combination, and move away” (Patrick Reusse, supra).

• Glen Flanagan, featherweight (126 lbs. max.), last recorded fight 1960, inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame 2005. Jim never spoke of the famous Gibbons brothers without also speaking of the pure greatness he witnessed in the gym and ringside in the Flanagan brothers, Del and Glen. Glen Flanagan had 120 recorded professional bouts with 84 wins (34 by KO), 23 losses, and 13 draws. “Every fight—everything in his career—was a war for Glen,” said Jim. “He was 5-7 and always fighting uphill, taking punches to get inside” (Patrick Reusse, supra).

• Don Weller, welterweight, last recorded fight 1962, the son of the proprietor and a member of the class of state champions who trained out of Weller’s Gym. He became the Minnesota professional welterweight champion in 1961. Don had 41 recorded professional bouts with 29 wins (9 by KO), 8 losses, and 4 draws. Emmett liked his son to work with the Flanagans, but Del was so good, it was frustrating. “You couldn’t get to him,” said Don in 2013. “I’d press inside and he’d tie me up time after time. Finally I told my dad that if he thinks working with Del is so great, go ahead but I’ve had it.” As for Glen, Don believed he had a fight plan that could get the win, but they never went beyond sparing.

• Jack Raleigh, promoter and longtime mentor to Jim. Raleigh called his promotion business the St. Paul Boxing Club, and his office was in Room 204 of the old Ryan Hotel at 6th and Robert (not far from the gym). An example of his boxing shows is the November 1955 card at the St. Paul Auditorium featuring Minneapolis’s Danny Davis, the state lightweight champ (135 lbs. max.), vs. Austin’s Jackie Graves, the state featherweight champ (126 lbs. max.). Graves won a ten-round decision. There were 4,000 seats offered at a dollar a seat, with the best seats going for four dollars. Boxrec.com reports the attendance at 1,480, with a gate of $2,877.03. So the average seat was two dollars. That was 1955. If you figure a conservative 4 percent annual inflation rate, the night’s gate in 2015 dollars might be about $29,000. The flyer advertising the fight promised all middleweights on the undercard: St. Paul’s Jim Perrault vs. Chicago’s Abie Cruze, Minneapolis’s Joe Schmolze vs. Chicago’s Rocky Volpe, St. Paul’s Terry Rindel vs. Al Johnson of Benton Harbor, Michigan, and Don Weller (fighting as a middleweight) vs. Milwaukee’s Ernie Ford (Don won this six-rounder on points). You know Jim was there that night, helping and learning from the master and man of integrity, Jack Raleigh. In the early 1960s, Raleigh tried to promote a big fight between Del Flanagan and “Hurricane” Carter. Jim was there when Flanagan demurred (Patrick Reusse, supra). There’s a good book on Carter by James S. Hirsch entitled Hurricane: The Miraculous Journey of Rubin Carter (Houghton Mifflin Company 2000). Raleigh owned the River’s Edge Restaurant on the Apple River in Somerset, Wisconsin, and became a loyal customer when Jim began selling for Jerry’s Produce. Murray McLean’s work Boxers of St. Paul includes the following note at the bottom right: “LETTERING BY MURRAY McLEAN Compliments of Jack Raleigh.” When Jim started his own boxing promotion business, he named it the All State Boxing Club, and Raleigh was his inspiration. See Round 13, entitled “The Businessman.”

In 1913, Minnesota had legalized six-rounders with eight-ounce gloves (Clay Moyle, Billy Miske: The St. Paul Thunderbolt, 13 (Win By KO Publications 2011)). If the Mike Gibbons Rose Room Gym opened in the Hamm Building in 1915 (the year the building was completed), and if it closed in 1949, it operated thirty-four years. For its part, if Weller’s Gym opened in 1947 and closed in 1968, it operated twenty-one years.

Full of gratitude, Jim was close with many of the characters these gyms produced over so many years, including Jack Gibbons, Ray Temple, Murray McLean, Billy Colbert, Emmett Weller, Del Flanagan, Glen Flanagan, Don Weller, and Jack Raleigh. Some were like a father to Jim, others like brothers.

Within St. Paul, there was a rivalry in Jim’s day. There were the fighters from the Rice Street area, led by Jim, against the fighters from the West 7th Street area, led by Joe Stepka. The press played up that there was no love lost between the rivals and their fans, but the bottom line was that these fighters were from the same city and naturally became lifelong friends. In 1988, Stepka was inducted into the Mancini’s St. Paul Sports Hall of Fame, of which Jim was then chairman.

Jim turned pro in 1945, glove fighting under the names Jimmy O’Hara and “Irish” and “Handsome” Jim. He was a proponent of the St. Paul style, a technique developed by Mike Gibbons.

“You would hold your left hand low and feint, making the other guy miss, and then you’d counter,” said Jim. “It was all in balance and timing” (Sean T. Kelly, “Remembering St. Paul’s Irish Boxers,” 13 Irish Gazette 4 (January–February 1998)).

The immortal Joe Louis put it this way, recalling the scientific boxer “Jersey” Joe Walcott: “When he dropped his left hand it wasn't a mistake. It was to feint you on to a right hand that could bring the roof on your head” (Joe Louis, “How I Would Have Clobbered Clay,”The Ring, February 1967, 40). In 1947, Louis got the win over Walcott but only by split decision. Walcott floored Louis in the first and the fourth.

Jim called the St. Paul style the “School of No Get Hit,” to set up the counter, in the manner of Mike Gibbons. Light-heavyweight Billy Conn, out of Pittsburgh, applied a similar boxing style when he challenged Joe Louis, the world heavyweight champion, in New York in June 1941, Jim noted (Sean T. Kelly, supra).

Conn almost pulled off what was thought impossible. After twelve rounds he had Louis on points. All Conn had to do was stay away from Louis for the rest of the fight. But then in the thirteenth, Conn got cocky, dropped his plan and his guard, and started taking chances with his punches. Louis saw the opening and retained the crown.

After a shower and some tears, Conn famously said: “What’s the sense of being Irish if you can’t be dumb?” (Randy Roberts, Joe Louis: Hard Times Man, Chapter 7 (Yale University Press 2010), Kindle Edition). Conn’s remark is on the list of the best post-fight lines (Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas, supra, at 205).

“Billy Conn was like lightning,” Louis recalled in 1967. “He learned his trade in the small clubs, from welter right through to heavyweight. He could have kept up with [Cassius] Clay because his legs knew where they were going”(Joe Louis, supra).

You’re guaranteed to enjoy the acclaimed book The Sweet Science (The Viking Press 1956) by A. J. Liebling. This book is on boxing’s list of required reading. In 2002, Sports Illustrated ranked it the number one sports book of all time. For his essays on boxing, Liebling was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1992. In the book, and specifically the essay entitled “The Big Fellows: Boxing with the Naked Eye,” Liebling describes Lee Savold, St. Paul’s adopted son, who faced Joe Louis in Madison Square Garden in June 1951. Louis scored a sixth-round knockout.

Liebling wrote: “Savold had said he would walk right out and bang Louis in the temple with a right. . . . But all he did was come forward . . . with his left low.” Unfortunately Liebling also wrote that Savold wasn’t much, wasn’t good, and even called him a “third-rater” and a “clown.” Imagine that. A Minnesota Boxing Hall of Famer, Savold had 150 recorded professional bouts with 101 wins (72 by KO), 42 losses, and 6 draws, including newspaper decisions. The British Boxing Board thought so much of him, they had recognized him as heavyweight champion of the world after his TKO win in the fourth over Bruce Woodcock in London in June 1950. Boxrec.com reports that the British recognized Ezzard Charles as the champ after the Louis-Savold bout.

Joe Louis is ranked number four on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time, after only Sugar Ray Robinson, Henry Armstrong, and Willie Pep. Billy Conn is ranked number thirty-five, Ezzard Charles number twenty-four, and Jersey Joe Walcott number seventy-nine (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, 10, 116, 76, and 267).

Jim hit “on the switch,” a sideways shift designed to set up a new attack. Using this technique, he surprised himself one night when he knocked out an opponent and woke him up with one too many punches. “I hit him again on the way down and I saw his eyes come open,” he explained. “I had him out and I woke him up. The guy got up and made a real scrap of it, but I still won, despite making extra work for myself” (Sean T. Kelly, supra).

A southpaw from birth, Jim boxed orthodox (right-handed), a holdover from the orphanage and elementary school where the good nuns didn’t tolerate the unorthodox. So he had an extrastrong left jab.

Blessed with inherited physical strength, Jim had a large torso made for punching with a long reach. They say his father, Herman Ehrich, could military press a small horse. Another story in the family has Herman knocking out a horse with a single punch. Herman died in 1977 at the age of 96, and he never needed a nursing home or any other help in that area.

They say Roberto Duran knocked out a horse with a single punch in Panama before he made it big (George Kimball, Four Kings: Leonard, Hagler, Hearns, Duran, and the Last Great Era of Boxing, Chapter 1 (McBooks Press, Inc. 2008), Kindle Edition).

Ranking Duran number eight on the list of the top one hundred fighters of all time, after only Sugar Ray Robinson, Henry Armstrong, Willie Pep, Joe Louis, Harry Greb, Benny Leonard, and Muhammad Ali, Bert Sugar called Duran “one of the most magnificent ring warriors of all time. And the greatest of the modern warriors” (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 23).

With the torso to be a big puncher, Jim wasn’t a heel-to-toer. (The puncher relies on planting his feet.) Nor would you say his style was that of a fighter. (The fighter’s weapons may include head butts, shoulders, elbows, knees, you name it.) As big and as street experienced as he was, Jim was a boxer. He had science. He’s known to have used his long reach to work the jab in combination with the right hook to keep his opponent off balance: jab—jab—boom, jab—jab—boom.

Round 6: The Boxer: Part II

The “Boston Strong Boy” John L. Sullivan's favorite punch was a right hook to the neck. In Mississippi City in 1882, the modern sports age began when he used it to acquire the title Champion of America from the “Trojan Giant” Paddy Ryan. “He had arrived in Mississippi City as John L. Sullivan,” says one author, “and departed as an American Hercules” (Christopher Klein, Strong Boy: The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan, America's First Sports Hero, Chapter 2 (Lyons Press 2013), Kindle Edition).

If a good jab is art, a good hook is power. Jim taught that punches need pop: “Don’t cock, pop.” When you cock, you leave yourself even more open. With the pop, there’s no wind up; you shorten your punches. He taught that other fundamental boxing skills—footwork, balance, feints, slipping a blow, timing, leverage, anticipating and recognizing the opening, space or distance management, clock management, clinching as necessary in tight spots—require patience. Patience in boxing means handwork, brains, and experience.

Beyond height (six foot one) and weight (200 lbs.), his physical pluses and minuses included a long face with a strong jaw, bull neck, and a large torso and arms. He had big fists, while his legs were strong but short for his torso. He had athletic-looking feet cursed with gout attacks from a young age. As a teenager, he was rejected from the United States Army, classified 4‑F, because of the gout.

He never espoused muscles for their own sake. He knew too many muscles could generate a “tell,” telegraphing what counter to apply at the vulnerable moment. He had an eye for seeing your tell. After discovering it, he told his manager: “Set the bout.” In terms of muscles, all in the fight game know, and Jim taught, that “It’s not what you got but what you can do with what you got.”

Jack Dempsey, commenting on his start as a light-heavy taking on the heavies, said: “It’s not about how much you weigh. It’s about getting your body weight in motion. That’s what a punch is, isn’t it? Body weight exploding into motion” (Roger Kahn, A Flame of Pure Fire: Jack Dempsey and the Roaring ’20s, Chapter 1 (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 1999), Kindle Edition). Dempsey is ranked number nine on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 10).

Sam Langford, ranked number sixteen on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time, commented: “Many fighters, when ready to hit, tighten their lips, half close their eyes, or give a tip-off in some way as to what’s going to happen” (Clay Moyle, Sam Langford: Boxing’s Greatest Uncrowned Champion, Chapter 3 (Bennett & Hastings Publishing 2013), Kindle Edition; Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 49).

When he was twenty-two, Muhammad Ali (then known as Cassius Clay) became heavyweight champion of the world by watching Sonny Liston’s eyes. “Liston’s eyes tip you when he is about to throw a heavy punch,” said Ali. “Some kind of way, they just flicker” (David Remnick, King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero, Chapter 11 (Vintage Books 1999), Kindle Edition). Ali is ranked number seven on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time. Liston is ranked number seventy-three (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 20 and 247).

Besides road work, Jim liked to play handball at the YMCA (both in downtown St. Paul and downtown San Francisco) as part of his training. A showman, he could dish out the prefight bravado. On the day of the fight, he preferred to spend the afternoon relaxing at a movie theater. He liked a good movie, as long as it didn’t have a message. His answer was no when Kitty inquired whether he was scared or nervous before a fight. He had trained. He had a fight plan. He had Murray McLean in his corner. He had his tough pa and six tough brothers and all his street fights and the Mike Gibbons Rose Room Gym as well as Weller’s Gym in his subconscious. He enjoyed the calm before the storm.

On the world-class level, “[Rocky] Graziano had a pre-fight smoke to calm his nerves” in July 1947 when he beat Tony Zale for the world middleweight title (Dave Newhouse, Before Boxing Lost Its Punch, Round 3 (ebooks 2012)). Graziano is ranked number ninety-eight to Zale’s number seventy ranking on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 336 and 237). Paul Newman played Graziano in the 1956 Oscar-winning movie Somebody Up There Likes Me.

In the glove era that saw Rocky Marciano as king of the heavyweight division, Jim was more often the hitter than the hittee, as he put it. Marciano himself provides a contrast that helps explain at least one reason why Jim had no illusions about being a contender for the world heavyweight crown. In the words of John E. Oden, “Rocky was frequently known to receive three to four punches with the hope of being able to deliver one” (John E. Oden, Life in the Ring, 123 (Hatherleight Press 2009)). Joyce Carol Oates put Marciano’s number at five: he “was willing to absorb five blows in the hope of landing one” (Joyce Carol Oates, On Boxing (HarperCollins e-books 2006), Kindle Edition)). By contrast, Jim believed that “if you’re taking more punches than you’re landing, you’re in the wrong business.”

As a disciple of Mike Gibbons’s School of No Get Hit, Jim meant no disrespect to the Rock, the first world champ in boxing history to retire with a perfect record, 49 and 0 (44 by knockout). Marciano boxed professionally from 1947 to 1956 (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 44–45).

Perfection aside, in day-to-day life, Jim witnessed firsthand the downside of a career in boxing. If you were in his sphere of influence, he recommended the School of No Get Hit even if, without it, you were racking up wins on the way to the top. He also advised not to quit your day job. Later he spoke of his experience:

There were a lot of fighters around when I was young, and everyone had cauliflower ears and busted noses. I saw a lot of broken people. When they were through with boxing, there was nothing left for them. I buried some of those guys. (Jim is quoted by Mike Mosedale, The Ring Cycle, April 3, 2007.)

The author Mark Kriegel called this state “Palookaville.” He wrote:

Palookaville, that punchers’ purgatory where broken boxers live in poverty and chagrin. They all seem to get there, one way or another, traveling the pug’s path from Kid to Bum. In Palookaville, the Ali Shuffle is a palsied jig. (George Kimball and John Schulian, At the Fights: American Writers on Boxing (Library of America 2011), which includes the writing of Mark Kriegel: “The Great (Almost) White Hope,” Kindle Edition.)

Despite his love of boxing and the allure of striving for the whole shooting match, Jim’s determination lay in building a future for his family, whether or not boxing penciled out. Faced with the family budget, he figured early that the best policy was to maintain a day job in addition to boxing. With this policy, born of street smarts, he found a level of independence not only in the beginning but ultimately throughout his six decades of fistiana. See Round 13, entitled “The Businessman.”

Like all boxers, Jim was taught that the gifted, like Mike Gibbons, and the overachievers, like Rocky Marciano, get to the top the same way: by training and training and training even more (Johnny Salak, Training a Full-Time Job, The Ring, August 1950, 46). The exception to the rule, like the partying Harry Greb, might never appear again.

Having done the math for himself, Jim accepted his place in the boxing equation. His regular day job meant he wasn’t set up to train full time, which meant he wasn’t training full time, which meant there’s no way he could become a contender at the highest level of the sport. No full-time training equals no contender material.

The great boxer Gene Tunney believed that “a good boxer can always lick a good fighter” (George Kimball and John Schulian, supra, which includes the writing of Gene Tunney: “My Fights with Jack Dempsey,” Kindle Edition). But Tunney wasn’t boxing when Rocky Marciano was at his peak let alone Jack Dempsey at his. On the famous Dempsey-Tunney fights of 1926 and 1927, see Round 2, entitled “Dignity and Sportsmanship.”

Muhammad Ali said of Marciano: “Rugged. . . . Could take a punch and just keep coming. . . . He beat up on opponents’ arms so they could not hold them up to defend themselves” (Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas, supra, at 18).

In the 1982 film Rocky III, the storyline has Rocky Balboa learning to become a boxer, rather than a puncher or fighter, in order to defeat Mr. T who depicts a killer in the ring. (Rocky Graziano’s birth name was Thomas Rocco Barbella.)

After over ten years in the ring, Jim had no prominent tell-tale signs. He certainly never experienced any eye problems or loss of cognitive ability, and his ears weren’t cauliflowered. On his face there were scars from the street and some from the ring. His fighting experience taught him that in boxing, and indeed in any adversarial situation, it’s an advantage to be underestimated.

His known pro matches are provided in Round 7, entitled “Boxing Record.” Many of his bouts are unknown, including his matches in San Francisco.

Kitty recalls that Jim was a popular local draw and the main event on the boxing cards. She remembers the auditoriums being full. He generally didn’t want her to watch him fight, but one night she showed up anyway and was sitting high in the stands where a man seated near her was yelling less than kind words. “Hey, that’s my husband,” she said to the guy, who was a gentleman after she’d identified herself. She remembers road trips to Jim’s fights, such as to Duluth in August 1953, the night Jim fought Don Jasper. Winning an unanimous decision in this boxer-puncher matchup, Jim was unmarked. He and Kitty and Murray McLean and the others in Jim’s corner enjoyed a celebratory dinner late that night.

As the 1940s came to a close, Jim enjoyed playing football in a recreational league. It was touch only, but of course, things could get rough. One play he was down field and a defensive back just leveled him. Back in the huddle, Jim said: “Run that play again.” The next thing you know, the defensive back is out cold. Jim said the rules were then changed to bar professionals of any sport from playing in the recreational league.

Recognized as a tough heavyweight, Jim also helped pay the bills by doing some professional wrestling. This form of athleticism became popular in Minnesota in the 1950s (George Schire, Minnesota’s Golden Age of Wrestling, 12 (Minnesota Historical Society Press 2010)). Jim could grab your wrist and apply pressure that instantly made you drop to your knees. “You wouldn’t want to fight him in a closet,” he quipped when he wanted to communicate that someone had good wrestling skills. After knocking out an opponent at practice one weekend, he never went back to pro wrestling as a young man. Thirty years later, he offered an ear and counsel to the Incredible Hulk Hogan, who delighted Minnesotans with live shows beginning in 1981. In Rocky III, filmed in 1982, Hogan “fights” Rocky for an entertaining charity event. (Hulk Hogan’s birth name is Terry Gene Bollea.)

In the early 1960s, Jim was late picking up one of his sons and his son’s friends from the St. Paul Armory where the boys enjoyed a professional wrestling show. They had time to goof around, and eventually they ticked off at least one of the wrestlers. As Jim walked into the Armory, all he saw was this imposing man threatening his son. Protective to a fault, Jim told the professional grappler: “You get in my boy's face again, I’ll stick your head up your ass and throw you for a hoop.”

The line “You wouldn’t want to fight him in a closet” and variations of the same is an old one. The scientific boxer, in contrast to the fighter who relies on making contact at close range, needs a larger ring for footwork. Doc Kearns and Jack Dempsey had had a falling out by 1926–1927 when Dempsey faced and lost twice to Gene Tunney. They say if Kearns had been in Dempsey’s corner, Dempsey would’ve come out on top. Kearns commented later: “You want the small ring, the sixteen-footer, because like I always tell people, inside is where Dempsey is Dempsey. If they fight in a broom closet, Tunney don’t see the second round” (Roger Kahn, supra, Chapter 12).

In 1915, Dempsey was coerced by a sheriff in southwestern Colorado to wrestle a local strongman called Big Ed. The sheriff claimed Dempsey owed back rent but would let him off if he wrestled. The sheriff also insisted that boxing was illegal. Without use of his fists, Dempsey was pinned in under five minutes (Roger Kahn, supra, Chapter 1).

Agility was one of Jim’s gifts. In the 1950s, he stopped by his cousin Tom Hoban’s house when some of Tom’s six kids were in the front yard. To entertain them, Jim did handstands. To top things off, he did cartwheels all the way to the end of the block and back. Eye-hand coordination was another gift. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Jim regularly shot the basketball off the backboard and into the net at the downtown St. Paul YMCA—from half court. The question wasn’t could he do it. The question was how many times in a row.

If he was a good athlete, he couldn’t carry a tune. He said he never envied any man but sure would’ve liked to have known how to sing. Heavyweight champion of the world Joe Frazier, who in the 1970s won the first of three battles with Muhammad Ali, loved to belt out songs. He explained:

Music has soul. It gives you a feeling of belonging. It gets you with life. It’s power, strength, and don’t think it doesn’t take stamina. That song routine I do is like real, tough roadwork. It moves every bit of you and the audience, too. The best thing is it’s real, it makes you feel you’re going places. Singing. That’s what I want to do with the rest of my life. Singing is what it’s all about. (Phil Pepe, Come Out Smokin' Joe Frazier: The Champ Nobody Knew, Chapter entitled “My Way” (Division Books 2012), Kindle Edition.)

Frazier is ranked number thirty-seven as compared to Ali’s number seven ranking on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 124 and 20).

Three hundred million viewers watched Ali-Frazier I, broadcast closed circuit to arenas and theaters around the world. The year was 1971, Madison Square Garden the venue, two undefeated heavyweight champions facing off, Frazier the victor. Of course, Jim was one of those viewers, and 1971 also was the year he quit drinking for good.

They may not articulate it, but boxers feel a connection to the immortals, even through others, and so Jim connected—indirectly—with Rocky Marciano and Sugar Ray Robinson.

Jim was a sparring partner for St. Paul’s Lee Savold, a heavyweight contender. There was no shame in Savold’s loss to Rocky Marciano in Philadelphia in February 1952. Marciano is ranked number fourteen on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time.

Jim also was a sparring partner for Joey Maxim, light‑heavyweight champion of the world, who beat New England heavyweight “Tiger” Ted Lowry in St. Paul in March 1952. Lowry had nearly 150 fights over his career, including a draw with Savold in 1947, and they say Lowry gave one of his best performances in St. Paul against Maxim. (Lowry had gone the distance twice with Marciano for a total of twenty rounds with the Rock.)

In June 1952, three months after his fight in St. Paul, Maxim successfully defended his title against Sugar Ray Robinson at Yankee Stadium. Of welter- and middleweight fame, the Sugarman wasn't able to take the light-heavy crown from Maxim. Sugar Ray Robinson is ranked number one, pound for pound, on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 1 and 43). You know as a scientific boxer who'd recently worked as a sparring partner for Maxim, Jim naturally felt a strong connection to Robinson vs. Maxim.

Joey Maxim was elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1994. He’s ranked number twelve on the list of the top defensive fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas, supra, at 161).

Jim became good friends with Joey Maxim, whereby Jim got to know Doc Kearns, Maxim’s manager. Kearns had managed not only heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey but also middleweight champ Mickey Walker and lightweight champ Benny Leonard. In December 1952, Archie Moore dethroned Maxim in a fifteen-round decision and thereafter Kearns managed Moore. In 1972, The Ring magazine, the Bible of Boxing, published its fiftieth anniversary issue in which it named the top ten boxing personalities of the previous fifty years. Kearns was named number three. The full list from number one to ten is Jack Dempsey, promoter Tex Rickard, Doc Kearns, Joe Louis, Max Baer, Muhammad Ali, promoter Mike Jacobs, Benny Leonard, Joe Frazier, and Primo Carnera (The Ring, June 1972, at 32–41).

Kearns was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990. A lightweight (135 lbs. max.), Benny Leonard is ranked number six, pound for pound, on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time. Mickey Walker is ranked number eleven, and Archie Moore is ranked number twenty-two (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 17, 33, and 69).

The Sugar Ray Robinson-Joey Maxim bout is the subject of the essay entitled “Kearns by a Knockout” in A.J. Liebling’s The Sweet Science (The Viking Press 1956). Here’s how Liebling drew his own connection to the class of immortals in the first essay in the book:

It is through Jack O’Brien . . . that I trace my rapport with the historic past through the laying-on of hands. He hit me . . . and he had been hit by the great Bob Fitzsimmons, from whom he won the light-heavyweight title in 1906. Jack had a scar to show for it. Fitzsimmons had been hit by Corbett, Corbett by John L. Sullivan, he by Paddy Ryan, with the bare knuckles, and Ryan by Joe Goss, his predecessor, who as a young man had felt the fist of the great Jem Mace. It is a great thrill to feel that all that separates you from the early Victorians is a series of punches on the nose.

Liebling believed television would put boxing into a coma. See his comments quoted near the end of Round 13, entitled “The Businessman.”

Another of Jim’s connections to the immortals was through fellow Minnesotan Don Jasper, whom Jim decisioned in 1953. The real McCoy, Jasper went on to face Ezzard Charles in 1956. Jasper was stopped in the ninth, but after all, he was fighting an immortal. Former heavyweight champion of the world, Charles is ranked number twenty-four on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 76).

Old boxers use the fight game in their everyday speech. Jim was no exception. Here are the top five lines he was known to joke with over the years:

1. There’d be two hits. Me hitting him, and him hitting the ground.

2. I’d hit him with so many punches, he’d think he was in a boxing glove factory.

3. The guy wouldn’t recognize the truth [even] if it jumped out and hit him in the nose.

4. The guy couldn’t punch his way out of a paper bag.

5. The guy couldn’t start a fight in an Irish saloon.

He also horsed around with the line that’s in every old boxer’s repertoire: “Now I want this to be a fair fight. So before we begin you need to know one of your shoes is untied. Boom!”

Old boxers always believe they have at least one good punch left. Jim felt the same, which is why he was comfortable carrying cash at all times regardless of his surroundings. There’s a story about Jack Dempsey along these lines:

In his early seventies, Dempsey was riding home one night when his taxi stopped at a light in midtown Manhattan. As it did, two young men opened the back doors on both sides of the cab, obviously bent on mugging Dempsey. Leaping out of the taxi, Dempsey hit one of the would-be muggers with a right cross from out of the past and then flattened his accomplice with his old patented left hook. (Jack Cavanaugh, Tunney: Boxing’s Brainiest Champ and His Upset of the Great Jack Dempsey, Chapter 23 (Ballantine Books 2007), Kindle Edition.)

Jim never had to use the punch he held in reserve, but once back when he was still jogging regularly, a would-be thief made the mistake of coming into the house in broad daylight. Kitty was shocked, and Jim happened to be sitting right there. He gave chase, catching the guy some blocks away.

If you’re big, tough looking, and walk like John Wayne, as Jim did, you stand out as a target for some unthinking younger fellow with something to prove, especially in the saloons. Lighthearted and compassionate, Jim didn’t want to hurt or embarrass you or ruin your clothes by pulling your shirt or jacket over your face. With his street smarts, Jim used double talk, if necessary, by which he began: “Where you from? You don’t say. You must know . . . Why I remember . . . ” Meanwhile, he made sure his back was covered and his feet had room. Pretty soon, more often than not, he had a new friend, or at least the guy returned whence he came without being hurt or embarrassed.

In one incident, the aggressors wouldn’t back down: two big farmers in a saloon not far from Lake Johanna (where Billy Miske used to live) and the present campus of Bethel University. Jim dropped them with two punches. He matched his right with the chin of the giant on the left and, swinging back, his left with the other big fellow’s chin, according to a witness who told the story to Jim’s son Gary.

You never heard Jim speak of his street fights. If you heard about them, you heard from witnesses who told stories after they discovered your relation. The stories illustrate nine words that are in every boxer’s DNA, certainly Jim’s: “You take a swing at me, you get popped.”

Another tale pits Jim against four in Gallivan’s Bar & Restaurant on Wabasha Street in downtown St. Paul. Suffice it to say, they were troublemakers. After leveling them, he carried them outside the rear exit, where he made it clear they weren’t to come back. A witness told this story to Jim’s son Jeff.

There’s also the story at Mickey’s Diner, the twenty-four-hour restaurant that resembles a railroad dining car in downtown St. Paul. In his early twenties, Jim and a buddy were entering the joint about two in the morning when his buddy saw two ladies around the corner. “I’ll be right back,” he said as Jim headed into the restaurant. Soon the buddy found himself on his back getting kicked pretty good by two fellows. The next thing he knows, Boom!, the assailant on his left was down and, Boom!, the assailant on his right was down, recalled the kickee to Jim’s son Gary. Over the years, Gary heard this story a dozen times if he heard it once, and each time the friend concluded with the words: “Jimmy picked me up, dusted me off, and bought me breakfast.”

The same friend learned you couldn’t accuse Jim of being an enabler. The venue for the lesson was a saloon on West 7th Avenue in St. Paul, where the friend got himself in another pickle. “Jimmy! Take care of him!” is what Jim heard, to which he replied: “I don’t know you.” Years later, his buddy grumbled he was sore at Jim for a long time over that deal, confirmed Bob Ritter, Jim’s son-in-law. For another twist where a friend set up Jim, see Round 14, entitled “The Storyteller.”

In the 1960s and 70s, Jim and his three sons belonged to the downtown St. Paul YMCA. When you entered the locker room there was the TV area to the left. Many a sport was viewed there thanks to ABC’s Saturday program the Wide World of Sports, what with its thrill-of-victory-agony-of-defeat intro. Next to the showers was the pool, where you swam nude except on Thursday’s family night. The basketball court was one floor up, next to the room with the rowing machines. The boxing ring was on a lower level.

Now there was a regular at the Y, a Golden Gloves middleweight champ in his day, who hounded Jim about getting in the ring. He was a close friend really. After a while, Jim figured the only way he was going to shut his buddy up was to get in the ring and make it just unpleasant enough that the fellow would never bring the subject up again. So that’s what Jim did, it worked, and they remained the same friends they were before they'd mixed with their fists.

If you played some baseball, you’ve taken your old mitt, put it up to your nose, and closed your eyes. You know the smell of that leather brings back memories like an old song. The Mike Gibbons Rose Room Gym and Weller’s Gym are gone, as are many of their patrons. But if you put some old boxing gloves up to your nose and close your eyes, you never know, images of the old days might just come alive.

Round 7: Boxing Record

It felt like one hundred degrees ringside in Duluth the night of August 27, 1953. Approaching his twenty-eighth birthday, Jim O'Hara was putting on a boxing clinic against a hometown favorite four years his junior. His opponent was none other than TNT-in-both-fists Don Jasper. Jasper could sock you to tomorrow.

Earlier the Duluth Herald had suggested that the victor of the evening’s main event would reign supreme in Minnesota, if only for a night:

Big Jim O’Hara, St. Paul, considers himself the No. 1 heavyweight fighter in Minnesota and has staged a claim on the championship.

Tall, handsome, hard-punching Don Jasper, Duluth, has his own ideas on the subject but prefers to do his talking with his fists.

These two knockout artists meet tonight in the national guard armory to settle what difference of opinion there is between them on the heavyweight title, and it promises to be a rugged argument.

Preliminaries will start at 8:30.

Members of the state boxing commission think enough of the scrap to be here en masse, having changed their regular meeting to Duluth. They will have dinner tonight in the Gitchi Gammi club.

O’Hara will have a decided edge over Jasper in ring experience but nothing on the Morgan Park scrapper when it comes to dishing out punishment.

Jasper has dynamite in both fists and proved to the satisfaction of local railbirds that he can take a punch as well as deliver one. He has worked harder for this bout than any of his previous ring appearances.

Their scrap is scheduled for six rounds but it’s a good bet it will end before that. (“Jasper, O’Hara Battle,” Duluth Herald, August 27, 1953, page 25.)

Perhaps more than any other fight, certainly from the vantage point of these many years later, the Jasper-O’Hara bout put a lasting shine on Jim’s reputation as a boxer. The St. Paul Pioneer Press reported the outcome thusly:

St. Paul’s Jimmy O’Hara, starting what he hopes will be one of his finest years, whipped Don Jasper of Duluth here Thursday night in the main event of a boxing card at the Armory.

O’Hara’s verdict was unanimous. The St. Paulite boxed well and displayed a good left jab that went in combination with a right hook that kept Jasper off balance throughout the test. (“O’Hara Beats Jasper in Duluth Test,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, August 28, 1953.)

If a unanimous decision means impressing the judges with your clean punches, your aggression, and your ring generalship, as they say, along with your defense, it was Jim’s night.

Per the lineal making of a champion, the boxing historian may note:

• August 27, 1953: Jim defeats Don Jasper in a six-round contest.

• October 27, 1953: Jack Wagner defeats Jim in a six-round meeting.

• January 10, 1957: Gene “Rock” White defeats Jack Wagner in a ten-rounder. White crowned the Minnesota heavyweight champion.

• October 29, 1957: Don Jasper defeats Gene “Rock” White in a ten-rounder. Jasper crowned the Minnesota heavyweight champion.

If Jim was never crowned the de jure heavyweight champion, there were plenty around who recognized him as having held the de facto Minnesota title. One was Don Riley, sports journalist and historian. He was inducted into the Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame in 2010 as a member of its inaugural class with the likes of the “Black Pearl” Harris Martin, Mike Gibbons, Tommy Gibbons, Glen Flanagan, Del Flanagan, Rafael Rodriguez, Scott LeDoux, Will Grigsby, Bill Kaehn, and Dr. Sheldon Segal.

Back in 1976 Riley wrote as only he could:

Finally, the state athletic commission has got a real boxing man on the panel. In the past they’ve leaned towards shoe salesmen, plumbers, stock brokers, sign painters and Avon drivers. True, Jim O’Hara qualifies as a produce executive. But he’s all boxing man. He’s a former state heavyweight pro champ who whipped Don Jasper in Duluth for the crown although there was a dispute that it was only a six-rounder and should have gone 10. But that’s not the point. Listen to his manager, venerable Murray McLean, look back:

"It was 100 degrees in the arena and Jasper could hit. But Jimmy out-hustled him all the way, jabbing and moving and fighting his way out of inside battles. Jim never asked who the foe was—only what time was the fight and what was the payoff. I handled Lee Savold against Jack Gibbons and the famous Lee was scared stiff for three rounds. He lost, too, because he was too cautious and tentative. O’Hara’s guts in Savold’s body would have made a super machine."

Jim, who has given hundreds of hours a year to the Golden Glove program, brings a fresh, honest integrity to the commission. As Murray McLean says, he won’t ask how tough is the problem, only say, "Let’s get at it."(“Don Riley’s Eye Opener,” St. Paul Sunday Pioneer Press, June 13, 1976.)

In all, Jim spent over a decade as a serious boxer, 1941 through 1953. He summed up his career in the ring by saying he won more than he lost.

In the winter of 1943–1944, Jim boxed in the Golden Gloves, winning the St. Paul tournament to become the light‑heavyweight champ (175 lbs. max.). He was the runner-up at what was then known as the Northwest Golden Gloves Tournament of Champions, which included Minnesota, and going into the semi-finals and finals of the tournament he showed promise. Louis H. Gollop wrote at the time:

In O’Hara’s case it is a question of whether the St. Paul boy can stand the gaff of fighting two tough fights in one night.

***

If he can weather the storm he appears as an almost certainty to win the title. (Louis H. Gollop, “Stepka, Lentsch, O’Hara Rated ‘Even Chance’ in Golden Gloves Finals,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, February 13, 1944, page 1 (Sports).)

If it was humiliating to be found unfit for military duty (classified 4-F) because of gout attacks, there was some consolation for eighteen-year-old Jimmy O’Hara in helping ten thousand fans of the sport of boxing take their minds off the war. The venue was the Minneapolis Auditorium, and in the semis and finals there were thirty-two remaining fighters in eight divisions, one representing the US Navy, three representing St. Paul, thirteen representing Minneapolis, and fifteen from outside the Twin Cities area of St. Paul-Minneapolis (“10,000 Expected for Golden Glove Windup,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, February 14, 1944).

Jim turned pro in 1945. If you Google “Boxrec.com” and “Jim O’Hara Minnesota,” you’ll find a summary of at least eleven of his professional contests. Unfortunately, at this writing entire years are missing from his record, including 1946, 1947, 1949, 1951, and 1952. It wasn’t him to save newspaper clippings or worry about whether he was getting credit for a fight in the history books. Back in the day, when The Ring magazine was at its zenith, you mailed in your verified boxing result to the editor, the famous Nat Fleischer. Neither Jim nor his manager mailed in any information.

Thankfully Boxrec.com provides at least a sampling of Jim’s record. The dates given also suggest that back then every day of the week was a good day for a boxing show.

Jim’s opponent in the first contest listed is heavyweight Jack Taylor, whose residence is given as Fort Snelling. So he must have been a soldier; no other information on Taylor is provided. They faced each other in Duluth on Friday May 18, 1945, and Jim got the win by knockout in the second.

Next he fought Earl Adkinson of St. Paul. His alias is reported as Erie; Jim knew him as “Early.” The contest occurred Friday June 8, 1945, at the St. Paul Auditorium. No weight is given for either man, but Adkinson is known as a light-heavyweight. As a welcome to the pro ranks, Jim was stopped in the first round.

He was nineteen at the time of the first bout listed. The ages of his opponents (other than Don Jasper and Jack Wagner) are unknown at this time. His bouts with Taylor and Adkinson are the only ones listed for 1945, and nothing is listed for 1946 and 1947.

Adkinson is reported to have retired in 1946 with a record of 8 wins, 4 losses, and 1 draw. He knocked out three others besides Jim. In October 1946, he decisioned middleweight veteran Don Espensen in a four-rounder at the St. Paul Auditorium. From Minneapolis, Espensen would retire in 1949 with 82 professional fights and a record of 42 wins, 30 losses, and 10 draws, including newspaper decisions. A newspaper decision is a bout left in the hands of the sportswriters. A draw, of course, is a bout neither fighter deserves to lose.

In the universal struggle known as making ends meet, Jim tried full-time fighting. It was the winter of 1947–1948. He’d arrived in San Francisco on a high horse, his brand new Chevy coupe for which he’d paid cash at the age of twenty-one. He made the trip with another boxer, believed to be a heavyweight, whom Jim helped manage while in California. Basically they managed themselves, taking on all comers.

Financial success from full-time boxing wasn’t to be. Jim saved money living at the San Francisco YMCA while training, only to be kicked out for fighting on the outdoor handball court. Eventually he sold the Chevy and found another way home. Back in St. Paul by the spring of 1948, he vowed anew to find and keep a full-time day job in addition to boxing. See Round 13, entitled “The Businessman.”

The details of Jim’s matches in San Francisco are unknown. His opponents are believed to have included tough sailors.

Jim next stepped into the ring, as recorded by Boxrec.com, when he was 22. His opponent was Willie Dee Jones, also of St. Paul, with the alias Piper. Standing six foot three and weighing in at 210 lbs., Jones boxed professionally from 1947 to 1956, including in California, Idaho, Utah, Iowa, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Florida. Jones would retire with a losing record (7–11–2) but when Jim faced him, he was on the positive side of the ledger. With only one W by KO, Jones was no doubt a scientific boxer who taught Jim a thing or two.

Jim faced Jones twice in 1948 and got decisioned in both of these four-rounders. The first occurred Sunday April 4, 1948, at the Minneapolis Auditorium. The second occurred five months later, on Tuesday September 7, 1948, at the St. Paul Auditorium.

Jim’s bouts with Willie Dee Jones are the only ones listed for 1948, and nothing is listed for 1949.

The next opponent listed on Boxrec.com is “Big Jack” Herman, who called Chicago his home. Born in Romania, his alias was Big Boy. Herman was six foot three and boxed professionally from 1949 to 1952, including in Florida as well as Illinois and Wisconsin. He has a 13–7 record. He must’ve been a terrific puncher. Of his 13 recorded wins, 11 are knockouts. But if you live by the sword, you die by the sword. All 7 of his recorded losses are knockouts.

Jim was twenty-four and faced Big Jack twice in a span of fourteen days in 1950. Jim took the first meeting, Thursday June 1, 1950, at the St. Paul Auditorium, knocking out Big Jack in four.

Big Jack didn't stay licked for long. He redeemed himself on Wednesday June 14, 1950, at the Hippodrome in Eveleth. (Today the US Hockey Hall of Fame Museum is in Eveleth.) The record suggests Big Jack scored a knockout, but there’s a note that the facts haven’t been confirmed. In this second meeting, Big Jack is listed at 215 lbs., while Jim is listed at 200. (Information on any rubber match has not been found.)

The next bout reported at Boxrec.com has Jim against Tony Gallus of Drummond, Wisconsin. Gallus boxed professionally in 1950 and 1951. The match occurred Wednesday September 27, 1950, at the Armory in Duluth when Jim was twenty-four. Jim outpointed Gallus in this six-rounder. Gallus is listed at 173 lbs., while Jim is listed at 180 even, though three months earlier he’s listed at 200 in his second match against “Big Jack” Herman. Gallus’s record is reported as 4–3, with 3 of his 4 wins by knockout.

Nothing is listed for 1951 or 1952.

For 1953, when Jim was twenty-seven, there are four matches listed at Boxrec.com. His opponent on Tuesday March 3, 1953, is Tom Tierney of St. Paul. The bout occurred at the St. Paul Auditorium. Jim won by technical knockout, and there’s a note that the round hasn’t been confirmed. Tierney is reported to have entered the roped square for pay in 1953 through 1955, with the outcome of a 0–4 record, all by KO.

According to Boxrec.com, Jim’s next opponent was Don Jasper of Duluth. They crossed gloves in Jasper’s hometown on Thursday August 27, 1953. Jasper was twenty-three years of age. As noted, Jim prevailed with a unanimous decision after six hard rounds.

Jasper boxed professionally from 1950 to 1959, including in Canada, Washington, Kansas, Michigan, and Wisconsin. He’s listed at six foot one and about 200 lbs. After Jim was able to get the best of him, Jasper went on a run of 11 wins and a draw. He was the real McCoy. In 1956, you know all of Minnesota was rooting for him when he faced Ezzard Charles, the successor to Joe Louis. Charles, who stopped Jasper in the ninth, is ranked number twenty-four on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time (Bert Randolph Sugar, Boxing’s Greatest Fighters 76 (The Lyons Press 2006)).

Jasper retired in 1959 after 39 pro fights, 27 wins and a draw against 11 losses. Sixteen of his wins were by knockout.

Jasper had become the undisputed Minnesota heavyweight champ on October 29, 1957, winning a ten-round unanimous decision over Gene White at the Ascension Club in Minneapolis. Known as the Rock, White is listed at Boxrec.com as six foot two and also about 200 lbs. Calling St. Paul his home, he boxed professionally from 1951 to 1958, including in Canada, Texas, Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. In 1993, White was inducted into the Mancini’s St. Paul Sports Hall of Fame, of which Jim was then chairman.

On Tuesday October 27, 1953, Jim faced Jack Wagner of Battle Lake. Both are listed at 190 lbs. With the alias Timberjack, Wagner was six foot three and twenty-three years of age. The match occurred at the St. Paul Auditorium. There’s a note that Jack Gibbons was the referee. He awarded Wagner a technical knockout at one minute and thirty seconds into the sixth round.

According to Boxrec.com, Wagner boxed professionally from 1953 to 1961, including a January 1956 fight in St. Paul against Ray Smude in which Jack Dempsey was the third man. Wagner has a 5–5–1 record, with all his wins by KO.

The O’Hara-Wagner bout is believed to have been Wagner’s first professional fight. ‘Twas a heck of a debut, before Jim’s hometown no less, especially considering that Jim had outboxed Don Jasper just two months prior.

Wagner never fought Don Jasper, but Wagner challenged twice for the Minnesota heavyweight title. He lost both efforts. In 1957, he battled Gene “Rock” White for the crown, losing by unanimous decision. In 1961, Wagner took on Don Quinn for the title, losing by KO in the second.

If Jim underestimated Wagner, no one else made that mistake. Don Riley wrote in 1976: “Jim O’Hara cautions boxers about carrying foes. ‘I carried Timberjack Wagner and they carried me out of the ring’” (“Don Riley’s Eye Opener,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, June 7, 1976).

According to Boxrec.com, White retired in 1958 with a 18–14 record. Eleven of his wins were inside the distance. Quinn retired in 1964 with a 23–10 record. Sixteen of his wins were short-route victories.

The final contest listed on Boxrec.com for Jim occurred Sunday November 1, 1953. His opponent was Joe Thomas, who’s listed at 186 lbs. No weight is given for Jim. The match occurred in St. Paul. Jim stopped Thomas in three, and there’s no record of any other Thomas fight.

Thus from the Boxrec.com information as reported in 2013, it appears Jim’s efforts produced a better than .500 record: 6 wins and 5 losses, about the same record as “Timberjack” Wagner’s. Of Jim’s 5 registered wins, 3 are booked as knockouts. By the same token, his inside gambles didn’t always pay off—it was lights out in 3 of his 5 recorded losses.

As mentioned, sportswriter Don Riley always called Jim state heavyweight champ for having whipped Don Jasper in Duluth in August 1953. If Jasper had had five fights under his belt when he faced Jim, “Timberjack” Wagner had had six fights under his belt when he faced Gene “Rock” White for the state heavyweight crown.

Leon Spinks had had only seven pro fights when he took the heavyweight title away from Muhammad Ali in February 1978. One of those, just four months earlier, was a draw with Minnesota Boxing Hall of Famer Scott LeDoux. (In September 1978, Ali regained the title from Spinks and a year later retired for the first time.)

It’s of course a time-honored tradition in boxing to lay claim to a crown, as is debate about who should have won this or that decision or who deserves to be on the list of the greatest.

St. Paul’s Mike Gibbons had a claim to the middleweight title after the death of Stanley Ketchel, the Michigan Assassin, in 1910 (The Ring Boxing Encyclopedia and Record Book 19 (The Ring Book Shop 1979)).

In his day, Ketchel was as famous as his heavyweight contemporary Jack Johnson. Elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990, Ketchel is ranked number nineteen on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time. Gibbons was elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1992. He’s ranked number ninety-two out of the top one hundred (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 60, 314, and 316).

Mike Gibbons is ranked number five on the list of the top defensive fighters of all time and number ten on the list of the greatest Irish-American fighters of all time. Bert Sugar put these last two lists together with Teddy Atlas (Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas, The Ultimate Book of Boxing Lists, 162 and 143 (Running Press 2010)).

In the early 1940s, Jim gave boxing lessons to his cousin Tom Hoban in the Mike Gibbons Rose Room Gym in the basement of the Hamm Building in downtown St. Paul. Having followed Jim’s career in the ring, Hoban in 2013 recalled two, and perhaps more, main events at the St. Paul Auditorium over the years between Jim and another St. Paul heavyweight, who he believed was Joe Stepka.

With the alias Bill Zaire, Stepka is listed at Boxrec.com as big as 215 lbs. He boxed professionally from 1944 to 1953, including in Nebraska, Illinois, and Michigan. You have to give Stepka credit for one-upping Jim in June of 1945. Whereas Earl Adkinson knocked out Jim in the first round at the St. Paul Auditorium on June 8, 1945, Stepka knocked out Adkinson in the first round in the same venue nineteen days later.

Jim and Stepka started out together in the St. Paul Golden Gloves, Jim then a light-heavyweight and Stepka a middleweight, where they became lifelong friends. In 1988, Stepka was inducted into the Mancini’s St. Paul Sports Hall of Fame, of which Jim was then Chairman.

Boxrec.com reports that Stepka retired in 1953 with a 24–10–2 record, including 13 wins by knockout.

Hoban said that the two bouts he remembers for certain between Jim and another St. Paul heavyweight, believed to be Stepka, were in the ring set up on the stage in the theater section of the St. Paul Auditorium, the same location where Hoban’s high school commencement was held. When asked the outcome of the rivalry, he said they were split. “They were pretty evenly matched,” said Hoban.

There’s nothing like a bout where the contestants are skilled boxers evenly matched. Boxing essayist A. J. Liebling describes a hard-fought eight-round draw he witnessed in New York City in the early 1950s featuring a couple of experienced welterweights (147 lbs. max.). Earl Dennis and Ernie Roberts were their names. Here Liebling gives us a glimpse of the regimented lives of professional boxers who hold day jobs:

I knew from talking with their managers that both Dennis and Roberts were married men and fathers, and that they both held down full-time jobs. Roberts, a clerk in a hardware store, got to work at eight each morning and left at seven. His employer let him have three hours off in the middle of the day, during which he trained at Stillman’s and had his lunch. After work, he went home to his wife and child, in Harlem, and at five the next morning he was in Central Park, doing his roadwork—five miles in about forty-five minutes every day before breakfast. He was twenty-five. Dennis, who was only twenty-two, although he had been married for five years and had two children, lived in Brooklyn and worked normal hours for a firm on the fringes of the garment center, making women’s belt buckles. After work, he went up to the Broadway Gym, a small place near City College, to train, and a couple of hours later headed for Brooklyn. He, too, did his roadwork in the mornings. Roberts had had about forty fights and Dennis about thirty-five. Their daytime bosses were at ringside.

A. J. Liebling wrote these words in the essay entitled “The Neutral Corner Art Group” in the book that Sports Illustrated ranked, in 2002, the number one sports book of all time: The Sweet Science (The Viking Press 1956). For his essays on boxing, Liebling was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1992. He believed television would put boxing into a coma. See his comments quoted near the end of Round 13, entitled “The Businessman.”

In the same essay, Liebling mentions how much these fighters, who like Jim maintained day jobs, were paid for their night’s work. He says they each received $300, less $100 for their managers. They fought in the early 1950s, as did Jim. So if you figure a conservative 4 percent annual inflation rate, their night’s pay in 2015 dollars might be about $3,028 gross before management fees.

If it weren’t for the drinking, Jim acknowledged, he’d have trained more. He said he never was Olympic material, for example, because of the late nights. Growing up around legends, he knew intellectually that with few exceptions, like Harry Greb, you don’t become a great fighter let alone a Mike Gibbons without dedicated training and training and more training. Applying that knowledge to yourself is the hard part, what with a life outside the ring.

Jim’s aim was to have a regular day job, marry Kitty (which he did in 1948), become a father (their first child arrived in 1951), and be the all-around family man (maintaining the family home and car, etc.) that he saw in his uncle, John Hoban. See Round 4, entitled “The O’Hara Name & St. Paul.” Needless to say, Jim also aimed to keep all his friends, including his drinking buddies. Consequently, he had plenty of excuses to cut his training short.

Insufficient training has long been a problem among gloved combatants (Johnny Salak, “Training a Full-Time Job,” The Ring, August 1950, 46).

A middleweight, Harry Greb is ranked number five pound for pound on the Bert Sugar list of the top one hundred fighters of all time after only Sugar Ray Robinson, Henry Armstrong, Willie Pep, and Joe Louis (Bert Randolph Sugar, supra, at 14).

A city boy, Jim appreciated the outdoors, at least as a spectator, not only in Minnesota but also in Alaska where he and Kitty visited family many times over twenty years beginning in the early 1980s. In Alaska, the vehicle of choice for getting to fishing holes and the rest is the small aircraft. But pilots often give up their wings if they don’t have the time to put in the hours necessary to stay sharp and on top of their game. In flying small aircraft, you need to see not only where you are but to anticipate miles ahead—as in boxing—what you can’t yet see, lest you get into a mountain pass where clouds can descend and sock everything in.

As of this writing, Boxrec.com has a record of 11 of Jim’s fights from June 1945 through November 1953. If he never trained like a contender, he’s believed to have had more than 11 professional contests. You don’t box at the professional level at least eight and a half years and have just 11 fights unless you’re Jack Dempsey. Jim had a family to support, and the heavyweights he faced were formidable, including the world-class puncher Don Jasper and a troika of six foot three-ers in Willie Dee Jones, “Big Jack” Herman, and “Timberjack” Wagner.

Having just 11 pro fights spread over eight-and-a-half years would be as risky as calling yourself a pilot on top of your game but having only 11 flights over about as many years. There’s no substitute for experience.

An intriguing clue suggesting Jim took on all comers is a remark by his manager, Murray McLean, who after all wasn’t making a living unless his men were fighting. “Jim never asked who the foe was, only what time was the fight and what was the payoff,” said McLean (“Don Riley’s Eye Opener,” St. Paul Sunday Pioneer Press, June 13, 1976).

Put it this way: in fistiana, you rest, you rust. Jim turned pro in 1945. As late as 1953, he didn’t show any rust when he whipped the great Don Jasper. So it’s likely understated to say Jim’s pro record consists of 11 performances.

Understatement is perhaps fitting. Sure on a trip to Duluth he’d mentioned to his son Jeff that it was hot in August 1953 when he fought in the Armory there. But that comment was about as close as he got to tooting his own horn about his boxing career. “Don’t use the word ‘I’ too much,” he advised. “It’s not about you.”

Talk about other athletes, those who were good like himself as well as the greats, now that’s when he got energized.

How did Jim, at six foot one and 200 lbs. in his prime, stack up sizewise with some of the heavyweight champs of the golden age of boxing? According to Boxrec.com: